Friends and fellow New Yorkers,

Let’s talk.

In New York City, a city of immigrants, we speak hundreds of languages around the five boroughs. Our languages and dialects tell the story of our diverse cultures and communities, and of a city built on these ideas and identities.

Now, Donald Trump is trying to deny those identities, and cut off those Americans, by not only declaring English as the official language of the country, but instructing the federal government not to provide aid in any other language. This will prevent many thousands of New Yorkers from accessing the federal government – and our city needs to do more to provide language support.

As we have seen, the Trump administration’s targeting of non-white Americans, especially immigrants, goes far beyond denying language access and into denying basic identity, existence, and human rights. Our government can help people learn English if they choose, not force them to abandon their language and cut them off from services. We have not just an opportunity but an obligation to strengthen language access in government and in our communities.

The city must make information accessible in a wide range of non-English languages. The reality, though, is that City Hall has not yet allocated the resources necessary to meet this mission across agencies, or in elected offices like my own.

Progress is not only possible, it’s being made. Initiatives like the City Council’s Community Interpreter Bank show recent strides toward bringing people into the conversation. At the same time, in a city of immigrants – many of whom we depend on daily, and in a moment like this, we can and must do more to demonstrate our commitment to communicating with the diversity of all New Yorkers.

This report lays out several ways in which the city can put our money where our mouth is and make sure no one gets lost in translation.

In advocacy,

Jumaane

Introduction

New York City has always been a city with an abundance of linguistic diversity. From the most commonly spoken languages to the most obscure dialects, they are spoken here, which makes New York City what it is: a culturally vibrant home for millions. Nearly half of all New York City residents speak a language other than English, and nearly a quarter possess limited-English proficiency (LEP), which is notable in a city and state with no designated official language.

On March 1, 2025, the Trump administration signed an executive order designating English as the U.S.’s national language. As the first official language designation in the country’s 250 year old history, this order revoked a 25 year old requirement for agencies to improve access to their programs for the more than 28 million LEPs in the United States. While this order was signed under the guise of strengthening American agencies, opponents of the order recognize it as an attempt to erase the multilingual identity of the American population. With such a linguistically diverse population and significant language needs in accessing city services, New York City must be a leader in ensuring linguistic equality and empowerment.

Within this context, New York City has sought to address an issue that continues to affect our friends, families, and neighbors: language accessibility. Language access permeates through every layer of society and its need is prevalent in virtually every aspect of life for many. The past few years of health crises, environmental emergencies, and thousands of new arrivals to our city further highlight the importance of language access and being able to communicate in-language. Language access bridges resource disparities, opens doors to opportunities, and ensures everyone’s voice is heard. In some cases, it can be the difference between life and death. Quality of life outcomes improve for LEP New Yorkers when language is not a barrier to entry, and the city is better for it, seeing social and economic benefits.

For years, NYC has implemented various language access laws, programs, and initiatives to further bolster its commitment to meet LEP New Yorkers where they are. As the most diverse city in the world, it is imperative that the city regularly reassess its provision of language services and constantly seeks to improve. This entails evaluation measures, listening and learning from New Yorkers (namely those LEP), and looking to adopt language access models that have seen success in other municipalities.

For the purposes of this paper, the focus of language access will be in relation to those with limited-English proficiency. However, we acknowledge that language and linguistic diversity goes beyond the abilities to speak, write, and read languages other than English - it is all the ways of communicating for those who are hard of hearing, nonverbal, those with cognitive conditions, possessing low literacy skills, and much more, and acknowledging that many of these identities intersect.

The City still has a long way to go, but it is making strides. With approximately four million New York City residents who speak a language other than English at home, and nearly two million that possess limited-English proficiency, it is crucial to maintain language access services to serve such a significant population of the city. Additionally, language access preserves the linguistic diversity that our city is known and revered for. In sum, to prioritize language access and language justice is to prioritize millions of people’s livelihoods and keep New York City the beacon of opportunity for all.

What is Language Access?

In order to comprehend the topic at hand, it is important to lay out key definitions to facilitate understanding throughout the course of this paper:

- Language access: Language access refers to the ability of individuals to communicate effectively and access information, services, and opportunities in their preferred language. This includes providing translated written materials and using interpreters for spoken interactions.”

- Accessible language: Language that accommodates people of all ages and abilities, including those with cognitive disabilities, people with low literacy skills, and speakers of English as a foreign language.

- Language justice: “Language justice is an evolving framework based on the notion of respecting every individual’s fundamental language rights—to be able to communicate, understand, and be understood in the language in which they prefer and feel most articulate and powerful. Rejecting the notion of the supremacy of one language, it recognizes that language can be a tool of oppression, and as well as an important part of exercising autonomy and of advancing racial and social justice.”

- Limited-English proficiency: When one does not speak English as their primary language and who have a limited ability to read, speak, write, or understand English can be limited English proficient, or "LEP."

- Interpretation: The conversion of information from one spoken language into another or between spoken language and sign language.

- Translation: The conversion of written materials from one language into another language.

- Plain Language: Plain language is clear, straightforward expression, using only as many words as are necessary. It is language that avoids obscurity, inflated vocabulary and convoluted sentence construction.

Language Demographics of NYC

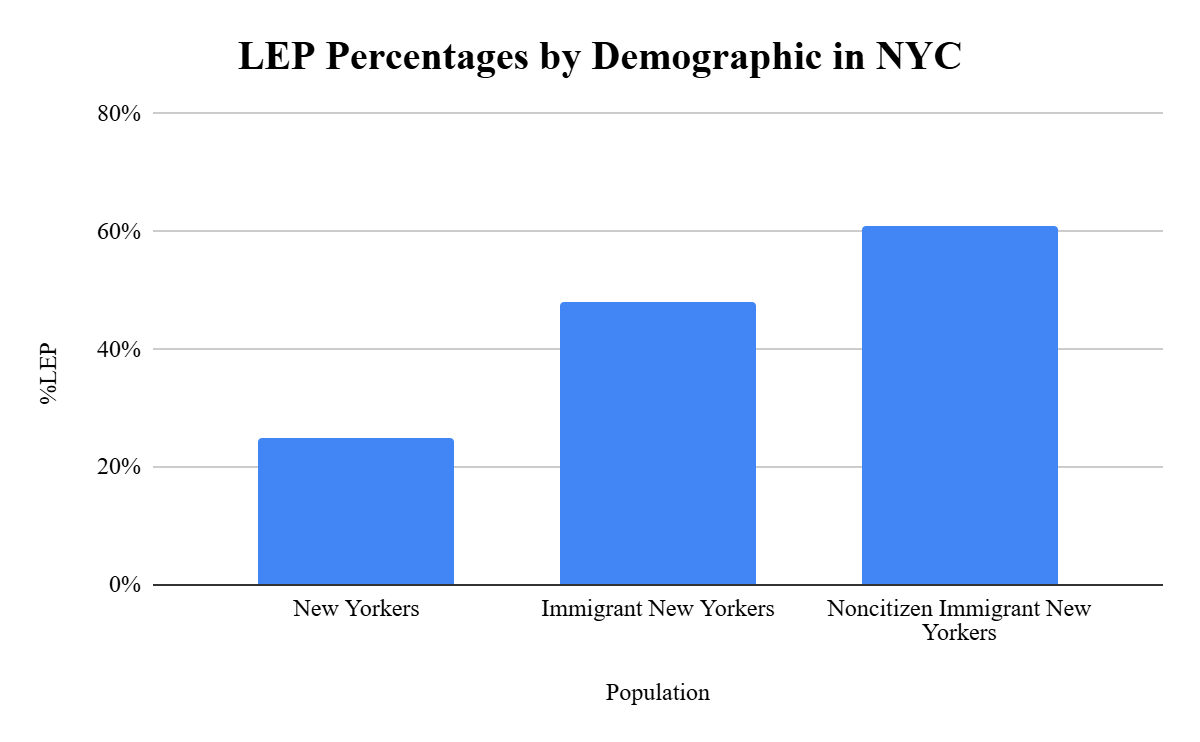

There are approximately 600 to 700 languages spoken in NYC and possibly more. According to the most recent Census figures, the top spoken languages overall in NYC are: Spanish, Chinese, Russian, French Creole, Bengali, Yiddish, French, Italian, Korean, respectively. Approximately 25 percent of all New Yorkers have limited-English proficiency and approximately 50 percent of New Yorkers speak a language other than English. Approximately 48 percent of immigrants are LEP. Nearly 61 percent of noncitizens are LEP.

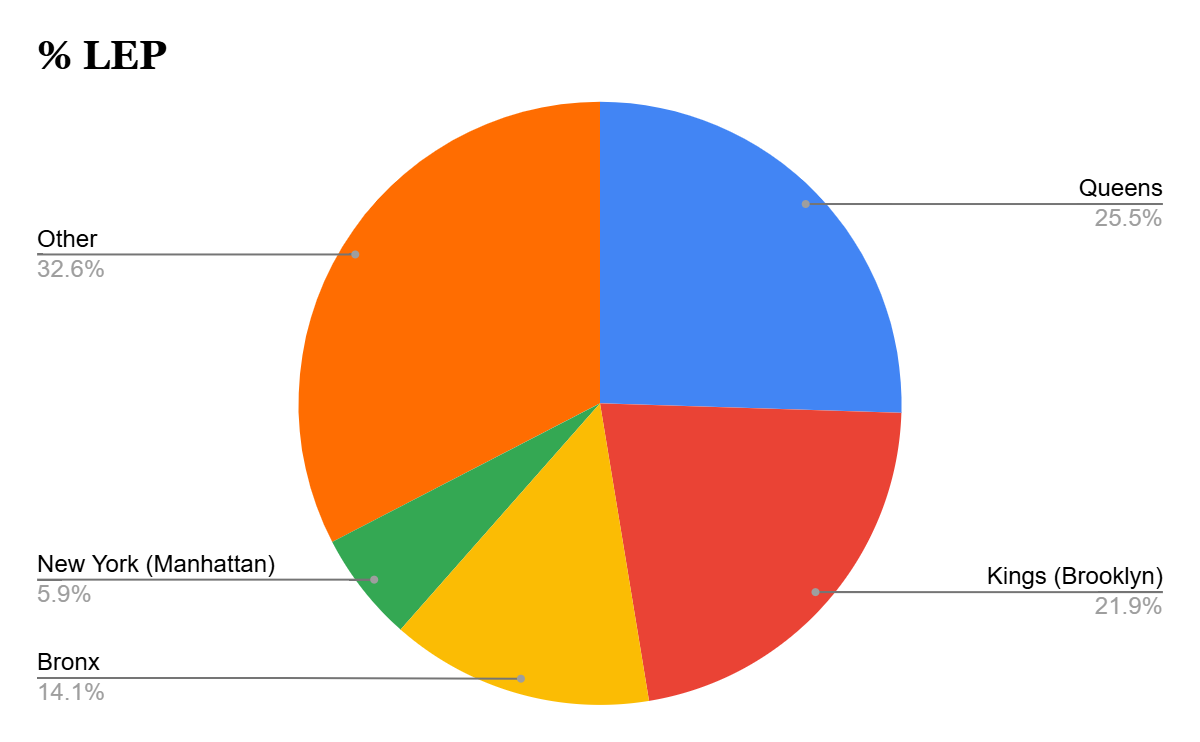

According to a recently published report by the New York State Office of Language Access, four of the five counties with the highest LEP population are located in New York City and account for 67% of the total LEP population in New York State:

- Queens County: 25.5% (636,627 people with LEP)

- Kings County: 21.9% (545,803 people with LEP)

- Bronx County: 14.1% (353,063 people with LEP)

- New York County: 5.9% (140,864 people with LEP)

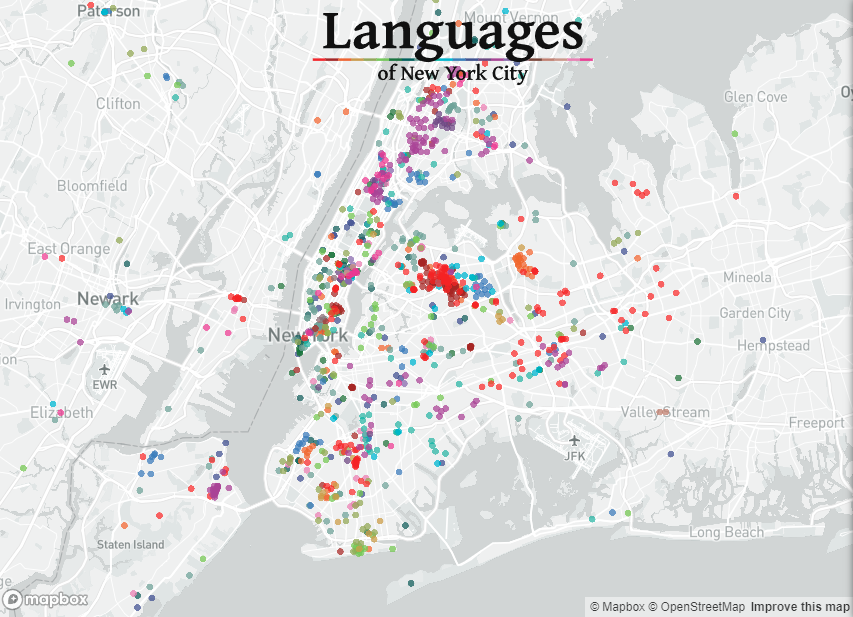

Additionally, more than 1.2 million New Yorkers speak a language at home that is spoken by less than 1% of the city’s population, per a 2020 report by the Comptroller's office. Languagemap.nyc is a comprehensive and navigable resource to provide further insight and visualization to the depth and breadth of New York City’s linguistic diversity.

The Present Landscape

City Agencies and Language Access

Local Law 30, enacted in 2017, is the City of New York’s comprehensive language access law (Appendix A provides a comprehensive list of all city laws and agency directives on language access.) Prior to its codification, city agencies were required to adhere to then-Mayor Bloomberg’s Executive Order 120, which required that all city agencies providing services to the public create a language access plan to ensure that those that do not speak English can still access city services in the top six spoken languages. LL 30 expanded upon that mandate, requiring additional language services to New Yorkers by city agencies. With over 200,000 new arrivals to the city in the past three years–some who have come and gone, but for the many who have decided to settle in NYC–language gaps are more noticeable than ever. Agencies’ adherence to the city’s language laws are crucial in aiding all New Yorkers to maintain a life that is safe, secure, and dignified.

When it comes to city agencies’ practices in abiding by Local Law 30 of 2017, they vary. In a review of more than 30 city agencies’ language access plans (LAPs)–which must be made publicly available and updated every 3 years–a frequent practice is to utilize internal multilingual staff first before moving onto third-party language vendors. Agencies emphasize that multilingual staff that opt to provide language services do so in a voluntary capacity. Some agencies also hold voluntary testing for staff competency in a language other than English.

The review of LAPs also identified several language vendors that various agencies contract with to provide language services. The majority of agencies have existing language vendor contracts and as a result, utilize their services more than relying on multilingual staff. Some frequently-used vendors include, but are not limited to:

- LanguageLine: For Fiscal Year 2023 (FY23) and Fiscal Year 2024 (FY24), had $91.9 million in active expense contracts.

- Accurate Communication: For FY23 and FY24, had $36.1 million in active expense contracts.

- Geneva Worldwide: For FY23 and FY24, had $13.4 million in active expense contracts.

- Eriksen Translations: For FY23 and FY24, had $5.3 million in active expense contracts.

Vendor contracts are important to highlight due to the sheer volume of translations and interpretation that occurs throughout the city and the associated costs it incurs. According to Gothamist, the city is seeing a trend of a growing bill for interpreters and translators, with over $35 million spent in 2023 spent on interpreters and translators alone—most of which is going to third party vendors outside of the city. As this trend continues, further insight into the efficacy of relying on external vendors—many of whom are not NYC-based companies—may be necessary.

The City’s Self-Evaluation Tool: The Secret Shopper Program

In 2010, under the purview of the Mayor’s Office of Operations (OPS) and the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA), the city’s language access secret shopper program (LASS) was created after EO 120 of 2008.

According to OPS, secret shoppers (who are recruited multilingual college and high school students) “visit more than 200 of New York City’s service centers to assess how well the centers provide services to customers who do not speak English…LASS secret shoppers visit walk-in service centers throughout all of the City’s five boroughs, pretending that they do not speak English and ask for information about the services offered. As part of their visits, secret shoppers also observe and rate interactions with frontline staff and security, determine the amount and quality of translated signage and documents, and assess the quality of interpretations, all while staying in character. At the end of the shops, secret shoppers, MOIA and OPS meet with agency managers and report on their findings. Where necessary, agencies take corrective actions.”

LASS serves as an informal review of agencies’ language access performance, and is not a formal inspection program nor audit. This is in part due to results being dependent on the languages spoken by secret shoppers, which vary from year-to-year. Secret shoppers—who are mostly teenagers or young adults—do not always fit the average client profile for certain agencies (e.g. Department for the Aging). As a result, the program has limitations when it comes to its scope of evaluation and results are not a comprehensive assessment measure. That being said, the program still provides valuable information for improvements in training, signage, and equipment, where needed based on what secret shoppers experienced. As of December 2024, the results of the secret shops since 2014 are publicly available on NYC Open Data.

Shortcomings

As the City continues to evaluate internal language access practices across agencies, particular events and incidents have highlighted the value of continuously improving and adapting to a changing landscape. Whether that be an influx of new arrivals speaking less common languages and dialects of those languages, or a global pandemic that led to many pivoting to virtual methods of communication, language access has been a lifeline for many through it all.

Health

In 2020, Covid-19’s presence in New York City led to citywide closures of storefronts, employers pivoting to remote work where possible, and students learning virtually for the first time. Amidst an ongoing health crisis, millions of people were trying to keep up with the latest health guidance across local, state, and federal lines. Medical institutions and providers were strained for resources, and as a result, language accessibility fell through the cracks as agencies prioritized quick turnaround of messaging, which were almost exclusively in English. For example, City Meals on Wheels, a member of the City’s vaccine taskforce, was tasked with distributing Covid-19 vaccine access information from the Department of Mental Health and Hygiene. The informational fliers arrived only in English despite the organization requesting fliers in additional languages, which never came. While city agencies did continue to improve amidst such shortcomings, the incidents emphasize the need to have language access plans that ensure agencies aren’t faced with the decision of prioritizing fast turnaround or waiting for documents to be translated.

Education

Covid-19 also led to a mass pivot to virtual work and learning environments, as individuals stayed inside to stop the spread, and quarantined if they were exhibiting symptoms. The NYC Department of Education was no exception, with over 1 million students learning online for what was likely their first time. Such change did not come without its challenges. LEP parents of DOE students faced a particularly unique set of challenges when it came to obtaining information they needed to keep their children engaged and learning throughout the pandemic. Without in-language materials, LEP parents were “unable to help their children access platforms, remote plans, instructional materials, and academic support.” As a result, their children suffer in the [virtual] classroom as well, and fall behind their peers.

The most prevalent challenges that remain in the day-to-day pursuit of educational language justice are due to widespread staffing shortages and underfunding in schools with a high density of newly arrived students and English Language Learners (ELLs). Many schools are unable to hire sufficient levels of bilingual and ESL-certified staff which present a key disconnect between ELLs and the critical resources that schools provide beyond the classroom, namely extracurriculars, tutoring services, and mental health counseling.

Disaster Response

Language access has also been shown to be crucial in other emergency situations, namely severe weather and environmental disasters. Every year, New York City faces various tropical storms and hurricanes, some stronger than others. One of the most deadly hurricanes in recent history was Hurricane Ida in 2021, which led to the deaths of 13 New Yorkers. Most of those deaths were immigrants of Asian descent with limited-English proficiency. Officials like New York Attorney General Letitia James suspect that a lack of in-language warnings contributed to these avoidable deaths. At the time of the Hurricane, severe weather alerts by the National Weather Service were only sent in English and Spanish. NotifyNYC, the City’s own emergency alert system, is available in 14 languages, but New Yorkers must first sign up in order to receive alerts. As emergency disasters continue to impact New York City, the city must grapple with its emergency preparedness systems and their respective shortcomings. Expanding language capabilities would be an apt first step in mitigating future deaths.

While the most poignant examples of the need for translated emergency notifications are apparent in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak and with the oncoming threats posed by climate change, in practice, specific flaws in the citywide emergency communications point to feasible solutions. Language lines for emergency communications are often unavailable after hours, leaving community-based organizations to shoulder the burden of targeted and translated outreach. Notifications from NotifyNYC and the National Weather Service, despite their efforts for translated services, still omit key languages from East Africa, Haiti, Burundi, and Madagascar, two of which make up a sizable portion of the LEP population in New York City. Providing adequate staffing levels and expanding language access during these emergencies are not only readily available solutions but also potentially a lifesaving measure for a city that will continue to wrestle with emergency response measures.

Housing + Social Services

In Spring 2022, New York City saw the start of an influx of new arrivals who were bused from the southern border and Texas. With a right-to-shelter mandate, New York City began to house thousands of new arrivals in addition to its existing shelter population. Dozens of emergency shelters were immediately set up to meet the growing demand of individuals seeking a place to stay. Eventually, reports of negligence, harassment, and abuse of immigrants from shelter staff came to light. By the end of 2022, the shelter system witnessed a handful of suicides linked to an inability to connect shelter residents with mental health resources. One of the difficulties in connecting individuals with the resources they could benefit from is language barriers. Newly arrived individuals in the shelter system, particularly Black immigrants who speak a variety of African and French-influenced languages, note challenges seeking social services as they speak languages that are not among the top ten languages in NYC. If information is translated, it is typically in Spanish, as the majority of migrant arrivals are from Latin American countries. However, that leaves out a significant non-Spanish speaking population who have to rely on community support and mutual aid. The same is frequently true for the nearly 200,000 indigenous immigrants in New York, some of whom speak Mixtceco, Nahuatl, K’iche, Maya ma’m, and Garifuna. This was formally addressed in a joint hearing of the NYC Council’s Committees on Immigration and Hospitals held on April 16, 2024. The seven and a half hour hearing yielded powerful testimony from recently arrived Black immigrants who identified language access as their primary barrier in accessing healthcare, housing, and education. In response, the NYC Council allocated funding in the FY25 City Budget to support the development of a Community Interpreter Bank, as well as the launch of three language services worker cooperatives focused on African, Asian, and Latin American languages. These initiatives aim to recruit, train, and dispatch community-based interpreters to meet the growing in-language needs across city agencies and service systems.

Civic Engagement

Language inaccessibility also impacts New Yorkers who have resided in New York City for years, including those who are United States citizens. Language access is important for all LEP New Yorkers regardless of immigration status and country of origin, and New Yorkers across a range of backgrounds face many of the same challenges. For LEP New Yorkers who are citizens, however, language access is an uphill battle at the ballot box. According to an exit poll conducted by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, 23% of Asian voters in New York City lacked access to interpreters and 39% were only offered English ballots in the November 2024 election. Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act mandates that states who meet certain population requirements provide language assistance to limited English proficient speakers. NYC has its own Civic Engagement Commission that is mandated to “expand access to language interpreters at poll sites throughout the city for limited English proficient (LEP) voters.” Ultimately, NYC is not in compliance with these statutes.

Public Safety

Effective, trusted, and timely communication is key when addressing issues of public safety. Since January 2025, the Trump administration has broken past precedent to pursue a heavy-handed mass deportation regime in the United States. The immediate threat that this poses to LEPs, regardless of citizenship status, is evident. Non-English speaking New Yorkers are especially vulnerable when interacting with law enforcement with whom they cannot effectively communicate. Language inaccessibility provides a whole host of challenges in law enforcement interactions which include racial and language profiling patterns, family separation as a result of federal enforcement crackdowns, and importantly, in accessing first responders during emergency situations.

An inability to effectively communicate with law enforcement is a primary factor in eroding the public’s trust in law enforcement. It is therefore evident that LEP New Yorkers are confronted with significant barriers when it comes to contributing to public safety and maintaining their personal rights during interactions with law enforcement. This is an exceptionally acute problem for delivery workers, or deliveristas, the vast majority of whom are LEPs and for whom the city has begun issuing criminal summonses on the basis of bicycle and e-bike traffic violations.

The American Judicial System

The judicial system in the United States, even for fluent English speakers, is not necessarily easy to navigate. When compounded with a system that is currently seeking to criminalize large swathes of New York City’s communities, the justice system can represent a nightmare for LEP individuals, regardless of the circumstances (medical emergencies, victims or alleged perpetrators) for which they are interacting with the system. As noted in the prior section, language inaccessibility is first a problem when interacting with law enforcement (often the beginning of all interactions with the legal system and its institutions). However, language inaccessibility when accessing legal services or appearing in federal, state, and local courtrooms present critical obstacles to LEP New Yorkers seeking justice. In practice, this leads to a higher level of vulnerability in resolving issues of housing, labor rights violations, immigration status, instances of medical malpractice, and many other injustices which are properly addressed via the legal system.

Developments

In the face of oversights and shortcomings, NYC nevertheless is progressing forward in improving language access. In 2023, Speaker Adrienne Adams, and City Councilmembers, recognized the language and service needs of recent arrivals and Black immigrants with the allocation of funding in the FY24 City Budget for the Language Access Workforce Initiative, led by the Language Justice Collaborative. This initiative funded the development of a Community Interpreter Bank and three additional language services worker cooperatives for African, Asian, and Latin American languages. These worker cooperatives are instrumental in recruiting, training, and dispatching community interpreters. With this funding, the Language Access Collaborative successfully launched “Afrilingual,” a worker-owned cooperative that provides language services in African languages including Arabic, French, Wolof, Fulani, Mandingo/Bambara/Dioula, Moore, and Ewe/Mina.

According to some city officials and language justice advocates, the current system of contracting with out-of-state companies is insufficient and LEP individuals end up relying on community members as a primary source for translation. These private companies are essentially competing against cooperatives like Afrilingual to secure city contracts. In the co-op model, hiring New Yorkers would allow that investment to go back into the city and ideally become sustainable. The commissioner of the Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs, also expressed his support for the city hiring Afrilingual: “I’d love to… We want to hire from within New York City.”

In FY25, the City Council restored funding for the Language Access Workforce Initiative, leading to the launch of the NYC Community Interpreter Bank in March 2025, a city-funded effort to increase language access and provide equal employment opportunities for bilingual and multilingual New Yorkers. Through the Interpreter Bank, the first Community Interpreter Training and Certification program was launched in partnership with Hostos Community College. The interpreter bank, which is the second in the nation, continues to provide language assistance in over a dozen languages, including the city’s ten most commonly spoken languages apart from English. Beyond its immediate impact of language educational and translation services, the interpreter bank has the potential to curb negative experiences of LEP New Yorkers when interacting with city government agencies, as evidenced by the Secret Shopper data.

With these two major strides in language access, what is needed to sustain such initiatives is ongoing investment from the city. Both the interpreter bank and worker co-op rely on city funding, which can drastically vary from year-to-year. In recent mayoral budget proposals, funding for these language services were nowhere to be found, and they would have gone unfunded had the City Council not advocated for them. As the city continues to move forward in language access, it must find ways to keep programs that support New Yorkers and are run by New Yorkers afloat.

Learning From Other Municipalities

As ways to bridge gaps in language accessibility evolve throughout time and amidst new developments, localities across the country have implemented their own language access plans and systems in relation to their respective LEP community needs.

Washington, D.C.: Interpreter Banks

Washington, D.C. was the first locality to launch its interpreter bank. Much like the NYC model, the interpreter bank is staffed and led by a local non-profit organization (Ayuda), and is funded by the city. DC’s interpreter bank is composed of the community legal interpreter bank and the victim services interpreter bank. The legal interpreter bank, first launched in 2007, supports low-income individuals who seek legal assistance in-language; the victim services interpreter bank provides victims of crime in-language support in their recovery. The interpreter bank is required to provide language services in the six languages identified by the DC Language Access Act (Spanish, French, Chinese, Korean, Amharic, and Vietnamese).

Mecklenburg County, North Carolina: Bilingual Pay

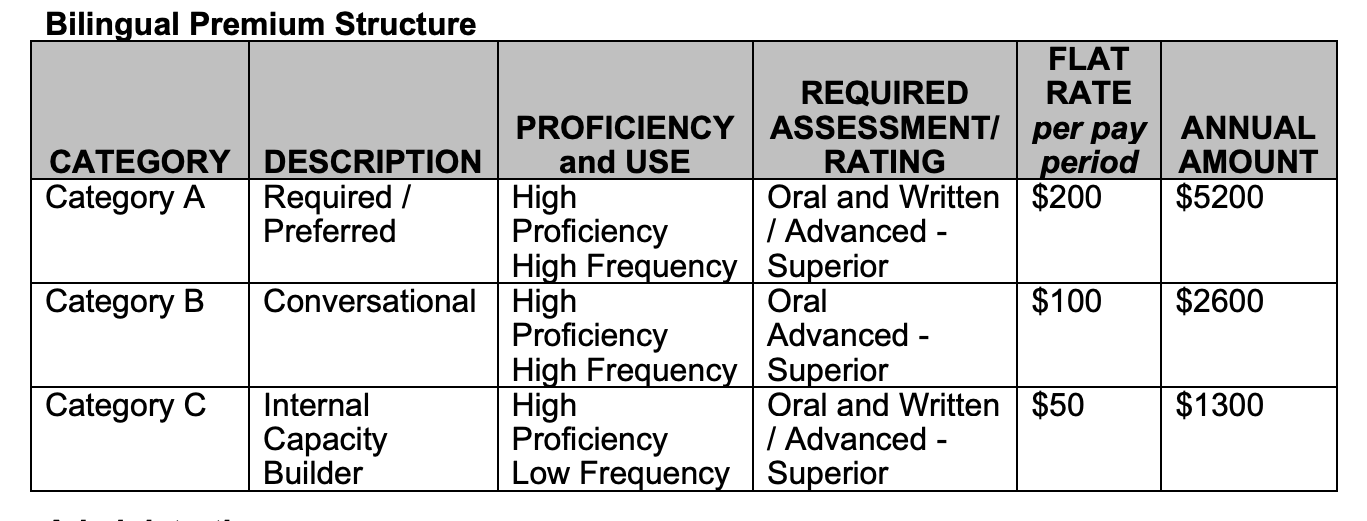

Mecklenburg County of North Carolina is one of several localities to institute a bilingual pay policy. A bilingual pay policy offers compensation for employees who are proficient in more than one language, after reaching certification or passage of a language proficiency assessment. Mecklenburg County, with a nearly-20% foreign-born population, established its bilingual premium program in 2008. As the county’s population becomes more diverse, “hiring and retaining employees with bilingual skills (especially Spanish/English), has become a necessity in order to provide satisfactory services to customers and clients… Bilingual employees provide valuable services to Mecklenburg County citizens above the normal scope of their job classification and the County recognizes this additional contribution.” In order to be eligible for bilingual compensation, employees must pass a language proficiency test by the county HR department through the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Acceptable proficiency levels are defined by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL). All employees are required to be tested.

There are three categories in the bilingual premium structure:

Prince George's County, Maryland: Education

Prince George's County Public Schools (PGCPS) first initiated interpreting and translation services in the district in 1993. Subsequently, the Office of Interpreting and Translation (OIT) was created in 2010. The OIT provides language access resources in a school district with more than 60,000 international families. PGCPS also has an interpreter bank with more than 100 on-call interpreters, covering over 20 languages, and a team of 6 translators for systemic and school-based translations. According to the district, more than 18,000 interpreting requests are completed annually.

Houston, Texas: Emergency Alerts

Houston, Texas has a population where one-third speak Spanish. There are three major Spanish language stations, each with a Translation Room where alerts are translated in real-time by certified translators. According to the Federal Communications Commission, the translation rooms “focus on ‘transcreating’ not ‘translating,’ mindful of being culturally competent in the wording and phrasing of the alerts… In preparation, they try to understand how and where the non-English speaking populations are consuming the data to improve the probability of getting the message to them. They attempt to hit all platforms with alerts multiple times.”

Minnesota: Emergency Alerts

During emergencies such as weather emergencies, the state of Minnesota delivers alerts in four languages (English, Spanish, Somali, and Hmong) over their emergency alert system. Minnesota also uses the Public Broadcasting Service to provide emergency alerting through its TPT-Now dashboard. The top four languages are prioritized due to its prevalence among non-English speaking communities. Alerts are also sent out through radio, Internet and some social media platforms. In order to expedite alert distribution in languages other than English, Minnesota customized culturally competent templates that can be quickly pushed out when an alert is received from government partners.

Conclusion

Language accessibility will constantly remain in flux as new developments—both expected and unexpected—continue to arise. In the face of varying levels of uncertainty, it is imperative that the City of New York commits to its mandate to provide language services to all New Yorkers. In a city as diverse as New York, where the hundreds of languages written and spoken contribute to its vibrant fabric, no New Yorker should be left in the dark due to language barriers. With recognition of pitfalls and shortcomings, and new developments to improve language accessibility, New York City can strive to be a leader in language access in the country and the world.

Recommendations

- Creation of an NYC Mayor’s Office of Language Access: In keeping with our prominence as an international hub, New York City should create a citywide “Office of Language Access” which will ensure compliance across city agencies with Local Law 30 and provide a paid interpreter bank for city offices staffed with fewer than 100 employees.

- Bilingual Services Compensation: consider implementing a bilingual compensation program for bilingual city workers across all city agencies. This may aid in retention of city employees and provide greater support in addressing LEP New Yorkers as language services can be provided directly from a city worker rather than through a third-party language vendor.

- Language Worker Cooperatives: expand the existing language worker co-op model to Asian and Latin American languages; scale up the existing Afrilingual co-op to include more African and French-influenced languages in other co-ops and allow for such co-ops to bid for city contracts, allowing NYC to hire from within, ensuring sustainability of the program and investment in multilingual New Yorkers. Having language co-ops for African, Asian, French, and Latin languages and dialects also ensures that languages not in the top ten as required by LL 30 of 2017 will be accounted for.

- Language Banks: ensure city funding for the language bank so that it can continue year-to-year. Ideally, language bank funding should be baselined in the city’s annual budget.

- Emergency Alerts:

- Schools: NYCDOE should consider implementing an interpreter bank model within the Office of Language Access.

- Weather and Health Emergencies:

- Develop customized in-language alert templates for emergencies, and ensure cultural competency and community trust in government resources in order to mitigate long turnaround times for translated information.

- Work with radio and television stations to air announcements in multiple languages.

- Work with community based organizations and churches to provide announcements in the frequently spoken languages of the community members they are engaged with.

Acknowledgements

Lead Author:

- Ana Luo Cai, Senior Policy & Budget Associate

Co-Author:

- Joseph Frankel, Legislative & Policy Associate

Additional support was provided by:

- Fabiola Mendieta-Cuapio, Civic and Community Empowerment Coordinator

- Rosie Mendez, Director of Legislation and Policy

- Veronica Aveis, Chief Deputy Public Advocate for Policy

- Wesley Paisley, Associate Counsel

- Mirelle Clifford, Deputy Digital Media Director;

- Kevin Fagan, Director of Communications

- William Gerlich, Senior Advisor for Communications

- Brittney Grimes, Press Officer

Design and Layout by:

- Luiza Teixeira-Vesey, Digital Marketing Specialist

Photos by:

- Caroll Campos

Special Thanks to:

The Language Access Collaborative and the New York Immigration Coalition for its collaboration with the Office of the Public Advocate in producing this report.

APPENDIX A

NYC Laws on Language Access

Year

Statute

Mandate

2003

Local Law 73, “Equal Access to Human Services Law”

LL 73 places language access service requirements on the Human Resources Administration, the Administration for Children’s Services, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and the Department of Homeless Services.

2007

Chancellor’s Regulation A-663 establishes procedures for ensuring that LEP parents are provided with a meaningful opportunity to participate in and have access to programs and services critical to their child’s education. Chancellor’s Regulation A-663 requires language services in the nine most common languages other than English spoken by parents of New York City school children.

2008

EO 120 requires that all City agencies providing services to the public create a language access plan to ensure that those that do not speak English can still access city services.

2017

LL 30 requires that covered city agencies appoint a language access coordinator, develop language access implementation plans, provide telephonic interpretation in at least 100 languages, translate their most commonly distributed documents into the 10 designated citywide languages, and post signage about the availability of free interpretation services, among other requirements.

2022

LL 48 amends the New York city charter and the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to expanding language access and requiring the inclusion of video content in the voter guide.

2022

LL 93 amends the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to supporting language access through a needs assessment examining language access services used by abortion providers and clients, and related recommendations.

2022

LL 98 amends the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to the identification of languages spoken by callers to the 311 customer service center.

2023

LL 6 amends the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to the capabilities of community-based organizations to provide language services to support city services.

2023

LL 8 amends the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to requiring certain agencies to publish guidance on responding to settlement offers, translate such guidance into the designated citywide languages, and notify settlement offer recipients about such guidance.

2023

LL 13 amends the New York city charter and the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to providing supplemental language access services in connection with temporary language needs.

2023

LL 14 amends the New York city charter and administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to enhancing language access for small business owners, and to repeal a related definition in section 17-1501 of such code.

2023

LL 15 amends the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to translation services for compliance materials.

2023

LL 19 amends the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to cultural programming relevant to prevalent spoken languages at older adult centers.

2024

LL 115 amends the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to requiring distribution of information regarding interpretation and translation services.

This report can be translated into over 100 languages at no cost. Please contact us at officeadmin@advocate.nyc.gov for more information.