To the incoming mayor and administration,

When I took office in 2019, one of my top priorities was addressing our city’s mental health crisis, individually and systemically. We released a report which was both a condemnation of the city’s mental health crisis response and a guide for restructuring and reforming those systems. We proposed a health-centered approach, and in the wake of several incidents when law enforcement shot and killed people in mental crisis, a focus on a healthcare response rather than a criminal one. In 2022, we published an update to that report, detailing improvements and shortfalls for mental health services in the intervening years.

Unfortunately, in the three years since our last review, the city and state have taken steps to further criminalize the mental health crises and its impacts – most recently, by expanding the criteria for involuntary hospitalization. This expansion is inherently worrying – not because there is no room for removal of someone who is a danger to themselves or others, a tool already available, but because the criteria and circumstances in which it can be used is unclear. We have seen the dangers in this moment of letting government agents remove people who can advocate for themselves. After the mayor and governor led this effort to remove people, rather than solve the underlying problems, Donald Trump pushed for even further criminalization of mental illness, homelessness, and poverty.

We have now been through two mayors since my first report, and seen far too little progress in the years since the original report was released. With the coming of a new era in City Hall comes a new opportunity for the deeper systemic change New Yorkers desperately need. This third installment of our review of mental health infrastructure in our city finds a need for action on existing proposals, as well as new initiatives which would help transform our ability to provide safety and support for people in greatest need, and for the entire city.

New York City already has many tools it is under-utilizing or under-funding to increase access to mental health services for vulnerable New Yorkers. Some areas have seen improvement—albeit often incremental—including the expansion of the B-HEARD pilot program and safe haven beds, and the national implementation of the 988 crisis hotline. The city has also expanded its supportive housing network, moving more people from shelter into permanent housing. At the state level, Governor Kathy Hochul is bringing more psychiatric beds back online. But there is still so far to go, and we are relying far too heavily on policing and incarceration to move people with mental illness out of public view.

There is an urgent need for state and local governments to take immediate action in light of the current federal administration’s dismantling of international and nation-wide resources. Broad cuts to social programs, including Medicaid; attacks on mental health services, such as eliminating the LGBTQ+ 988 crisis line; and threats to federal funding for New York City and State make the future of mental healthcare uncertain and precarious.

There are no easy solutions to this crisis – that much is clear. What’s also clear, though, is that trying to criminalize or conceal this mental health emergency is both immoral and ineffective. I urge you to take a real look at the issue, and at these recommendations, so that when you take office in January we can finally move forward with the urgency this crisis demands and New Yorkers deserve.

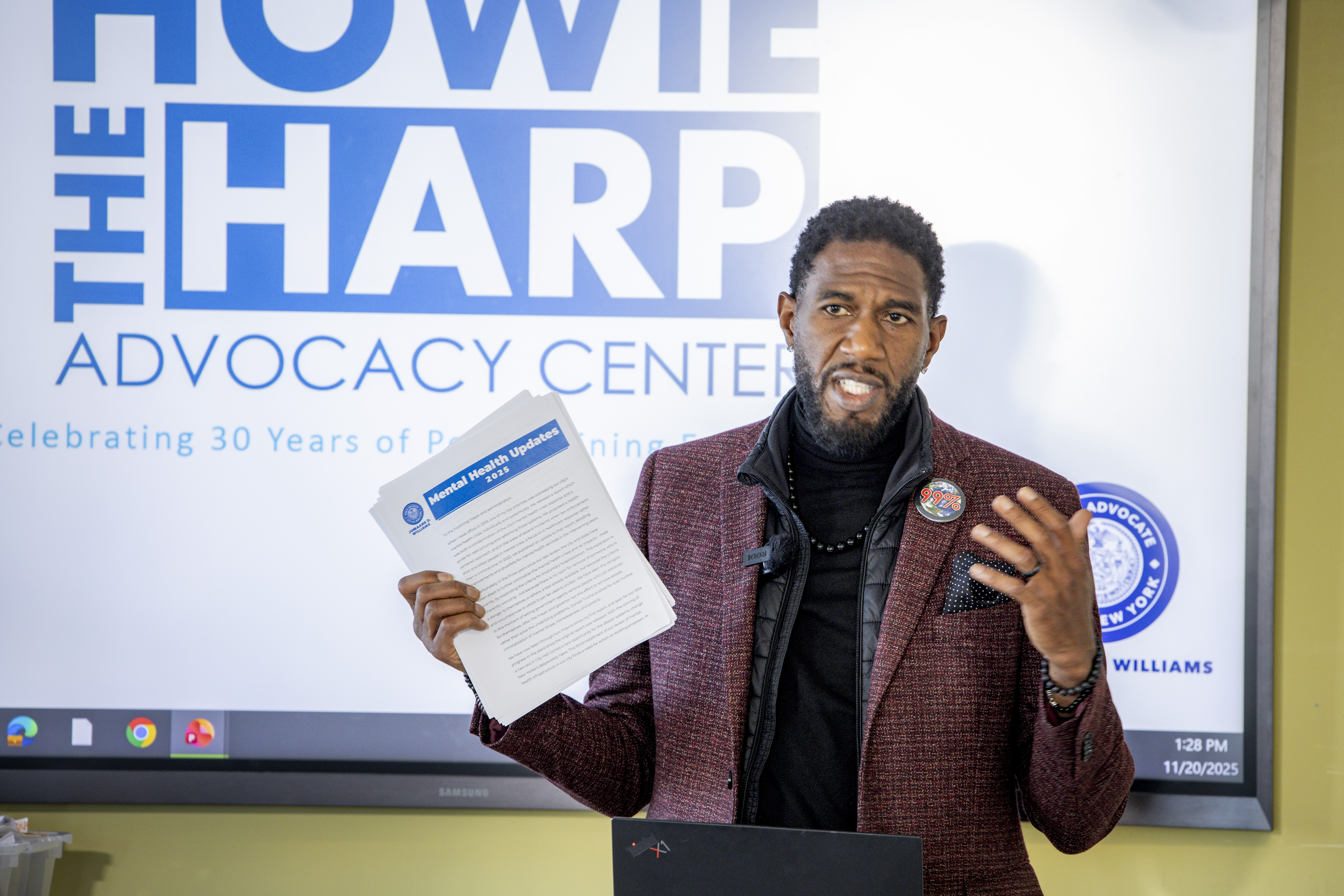

Sincerely,

Jumaane D. Williams

Public Advocate

Reducing the Number of Mental Health Crises Requiring Emergency Response

Respite Care Centers

Report Recommendations (2019)

Respite Care Centers are an alternative to hospitalization for those in crisis and provide temporary stays in supportive settings that allow individuals to maintain their regular schedules and have visitors. Trained staff, as well as peers and non-peers, respond and provide solutions to crises. The city must increase funding for existing respite care centers and develop new sites in areas with a high volume of 911 calls. In 2019, there were 8 centers operating in NYC.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

As of 2022, there are 4 Health Department community partners operating respite centers serving adult New Yorkers, a drop from the 8 centers in 2019.[1] The Administration for Children’s Services also operates a respite program for youth.[2]

Additional Recommended Action (2022)

This decrease in respite centers is deeply concerning. They are largely led by community based organizations. As a result, we are renewing our recommendations to expand the number of respite centers and increase funding to community partners who run them. In 2021, we called for a $5.2 million allocation to respite centers. Centers must be peer-led, allowing individuals to be supported by those who share similar lived experiences.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

Local Law 118 of 2023 required the Mayor to establish four new crisis respite centers.[3] As of 2025, there are 11 respite centers in New York City, with one in the Bronx, four in Brooklyn, three in Manhattan, two in Queens, and one in Staten Island.[4] This is a much needed increase from 2022. The Administration for Children’s Services also operates a respite care program that provides 21-day respite services to persons in need of services (PINS) and justice-involved youth at risk of detention or placement.[5] The Mayor and City Council invested $3 million in the Fiscal Year (FY) 2026[6 - The fiscal year for the City of New York commences on July 1st and ends on June 30th. The number of the fiscal year indicates when the fiscal year will end. Therefore Fiscal Year 2026 runs from July 1, 2025 to June 30, 2026.] budget to support expanded operations of crisis respite centers.[7]

Drop-in Centers

Report Recommendations (2019)

Drop-In Centers are multi-service facilities for unhoused New Yorkers that provide a variety of services including food, social work, and referrals to needed programs.

The city must expand the number of drop-in centers, including the development of at least one in Queens which does not exist as of 2019. Five drop-in centers exist in the city as of 2019.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

Drop-in centers for adults have increased from 5 in 2019 to 7 in 2022, with 1 in Queens, 2 in the Bronx, 2 in Manhattan, 1 in Brooklyn, and 1 in Staten Island.[8] Under the Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD), there are separate borough-based drop-in centers serving unhoused youth ages 14 to 24.[9]

More drop-in centers should be developed in order to increase access to centers for unhoused New Yorkers across all five boroughs. Drop-in centers must ensure they are providing mental health referrals as needed, helping the unhoused with a pathway towards permanent housing, and remain operating 24/7.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

The number of drop-in centers for adults has decreased from seven in 2022 to six in 2025, with one in Queens, one in the Bronx, one in Brooklyn, two in Manhattan, and one in Staten Island.[10] All of the drop-in centers are open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. DYCD operates seven youth drop-in centers for those ages 14 to 24, with three in Manhattan, one in the Bronx, one in Brooklyn, one in Queens, and one in Staten Island.[11]

In 2024, the annual count of people sleeping on New York City streets was the highest in over a decade.[12] Despite this, at least one drop-in center—Mainchance located in Manhattan—was threatened with closure last year by the Mayor Eric Adams’ Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG), though it ultimately remained open.[13] Drop-in centers, which are often points of entry to access housing, employment, and medical and mental health services for people who are unsheltered, are even more critical with such a large population living on the streets.

Mental Health Urgent Care Centers

Report Recommendations (2019)

Mental health urgent care centers would provide people experiencing a mental health crisis with a short-term alternative to a hospital, with services specifically tailored to the mental health concerns.

The city should implement mental health urgent care centers throughout the city. As of 2019, they have yet to be implemented.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

The city has implemented facilities similar to the urgent care models adopted in cities like Los Angeles. In 2020 and 2022, two behavioral health facilities—called Support and Connection Centers—opened in East Harlem and the Bronx. They are meant for short-term treatment and stabilization for people experiencing mental health or substance use needs and serve as an alternative to emergency room visits that may have longer wait times and law enforcement intervention.[14] For 17 months, from October 2020 until March 2022, there were 318 visits to the East Harlem SCC, then operating at limited capacity due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[15]

Status of Recommendations in 2025

As of 2025, New York City has one Support and Connection Center (SCC) that is located in East Harlem. The SCC is operated by Project Renewal in partnership with the Department of Health and Mental Health (DOHMH) and can take 18 clients at a time. Since 2023, it has served 850 clients.[16] A second SCC in the Bronx was previously announced, but DOHMH testified to the City Council in May 2025 that it had been cut under Mayor Eric Adams’s program to eliminate the gap (PEG).[17]

While New York City’s Health + Hospitals (H+H) operate emergency psychiatric services, including for children and adolescents,[18] visiting an emergency room carries the risk of long waits and involuntary commitment, and many inpatient units can have far more patients than SCCs, which serve a small number of clients at a time to provide more personalized care. The stays are shorter—up to five days at Project Renewal—which may encourage those fearful of long-term involuntary commitment, who may be hesitant to visit an emergency room, to utilize their services.

The city should restore $5 million in funding for the Bronx Support and Connection Center and fund SCCs in Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island as well.

Safe Havens for those with Mental Health Concerns

Report Recommendations (2019)

Safe havens are a type of immediate temporary housing for homeless individuals that offer supportive services, including mental health and substance abuse programming. Notably, individuals are not required to be sober upon entry or during their stay and individuals are typically referred by homeless street outreach teams rather than the city’s central shelter intake system.

The city must increase funding and the number of safe havens in New York City. As of 2019, there are 10 safe haven locations with a total of 667 beds.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

In March 2022, a new safe haven site was opened in the Bronx with 80 beds.[19] Mayor Adams announced investments into safe haven shelters the following month, with the money going to fund 1,400 beds in smaller facilities. The new funding would bring the total number of stabilization and safe haven beds to more than 4,000.[20] The significant commitment in investing in safe havens by the city is promising, and we must keep the city to their word and ensure over 4,000 beds are available and accessible, that they run 24/7, conditions are habitable, and they are well-staffed, with adequate funding to bolster these outcomes.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

As of November 17, 2025, there are 2,014 individuals in safe havens. In Mayor Eric Adams’s 2025 State of the City address, he announced a $650 million plan to support people experiencing homelessness and severe mental illness.[21] This included adding 900 safe haven beds on top of the existing 4,000.[22] A 2023 report by the Comptroller’s Office found 25 safe haven locations at the time of publication, with none directly operated by the Department of Homeless Services.[23]

According to Department of Social Services Commissioner Molly Wasow Park, those placed in safe havens typically stay inside longer and have a higher rate of connecting to permanent housing than those in the broader city shelter system.

Yet the majority of clients still leave safe havens without a permanent placement.[24] This is an issue for anyone within this system who struggles to connect to a home of their own. The bottlenecks that clients experience are driven by the bureaucracy of the applications process, acceptance of vouchers, and scarcity of affordable housing stock. Outcomes need to improve to encourage engaging or continued engagement with the city. The various NYC agencies should prioritize making paperwork more seamless and working with landlords to accept vouchers to ensure more New Yorkers have their housing needs met. The vacancy rates in the Department of Social Services, amongst the highest in the city, exacerbates the process and its impact cannot be adequately measured.[25]

Supportive Housing

Recommended Action (2022)

Fund and expand supportive housing,[26] providing the groundwork for unhoused individuals with a pathway towards permanent housing and immediately available, continuous comprehensive services. Currently, the city is lagging behind in providing supportive housing, with a long and often-delayed application process.[27]

Status of Recommendations in 2025

According to an April 2024 report by the Supportive Housing Network of New York, there were 40,472 units of supportive housing in New York City, and 21,827 units outside the city, at the time of publication.[28] About half of New York’s supportive housing units are in congregate residences, where staff work onsite to directly provide services to tenants, while the other half are scattered site, where units are rented on the private market and tenants receive mobile services in their homes. In FY2024, there were 9,678 unique individuals or families with an approved supportive housing application, but 3,318 were still awaiting a placement at the close of FY2024.[29] The city should also, wherever possible, place people in supportive housing in their communities; moving a person far from their neighborhood where their loved ones live and they may be connected to treatment or other community resources only destabilizes a person further. There’s no telling how agency vacancies impact city services, but higher caseloads and lengthening of processing time is a likely natural outcome.

Mobile Crisis Teams

Report Recommendations (2019)

As of 2019, there are approximately 24 Mobile Crisis Teams (MCTs) across Brooklyn, the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens. Mobile Crisis Teams can only be accessed through the 11-digit long NYC Well phone line and online form. MCTs do not have the resources to respond immediately to crises, instead responding within a 48hour window of time from when the initial referral takes place. They also respond to urgent but non-emergency situations that otherwise would call for police.

Research should begin on how the city can integrate non-police MCTS to the 911 dispatching system. The city must increase funding for the Mobile Crisis Team program so that response times can improve. The city should explore partnerships with local community-based organizations (CBOs) to further this aim.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

As of 2022, there are 19 adult MCTs serving the 5 boroughs. To request an MCT, an individual still needs to call 888-692-9355, text “Well” to 65173, or utilize NYC Well’s website. “MCTs aim to respond . . . generally within several hours of receiving the referral.” MCTs also generally do not work with people who are street homeless.[30] This year, the New York State Office of Mental Health invested $10.8 million into NYC Well for increased staffing and capacity, allowing “NYC Well counselors and peer support specialists to answer up to 500,000 calls, texts and chats from New Yorkers between July 2022 and June 2023.”[31]

As it stands, there is no full-scale integration of MCTs and the 911 dispatching system. Referrals to MCTs through NYC are often not immediately responded to and are not for emergencies, but situations to be addressed urgently. MCTs also generally do not work with people experiencing unsheltered homelessness; this means that a concerned person seeking assistance for a person sleeping on the street or in a subway station has few options aside from calling the police.[32]

The state’s investment must also go towards boosting the number of MCTs, placing MCTs in locations that have a greater need for mental health support, and expanding operating hours beyond the 8AM-8PM time frame that currently exists. To expand accessibility, NYC Well should implement a shorter direct-line phone number to call and utilize CBO partnerships to expand the range of EMT dispatching if necessary.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

There are still 19 MCTs that serve adults aged 21 and older across the five boroughs.[33] Each borough has one MCT that serves those under the age of 21. MCTs still operate 8 am to 8 pm, 365 days a year. To request a referral to MCT services, New Yorkers can call 988, though 988 does not operate MCTs; rather, MCTs are operated by hospitals with state-licensed Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Programs (CPEPs) or psychiatric emergency rooms or by community-based organizations designated by DOHMH. MCTs typically respond within a few hours of a referral, and are not intended for emergencies, but to be addressed urgently. Still, without a 24/7 operation and adequate staffing, these services won’t reach the desired populations. The city must expand the number of MCTs and the hours they operate.

Create a Non-Police Emergency Number

Report Recommendations (2019)

We recommend New York City create an alternate non-police department number to call for those in mental health crisis to get urgent immediate treatment. New York City must research and evaluate models for responding to 911 calls that do not involve the police.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

911 remains the default number to call for those in mental health crisis.

988 was nationally instituted in 2022 as the 3-digit number for the already-existing suicide and crisis lifeline for those “experiencing suicidal, substance use, and/or mental health crisis, or any other kind of emotional distress.” However, it has been reported that many calls originating from 988 end up being rerouted to 911 anyway.[34]

The city has called on the federal government to resolve geolocation issues with 988, as currently, calls are rerouted based on the caller’s phone area code rather than geographic location.[35]

Status of Recommendations in 2025

This year, the non-profit organization that operates the city’s 988 hotline reported that it would have to lay off up to a third of its staff due to a more than $10 million shortfall.[36] Parts of the hotline have come under attack from the Trump Administration, which has ended the specialized prevention services for LGBTQ+ youth from the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, though callers can still reach an LGBTQ+ crisis hotline by calling The Trevor Project directly.[37] In the FY2026 budget, Mayor Adams and the City Council invested $5 million in funding to 988 to protect suicide prevention for LGBTQ+ New Yorkers.[38] Still, crisis workers in New York and New Jersey expect to lose their jobs after the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a federal agency, announced it would no longer be funding the option to be routed to LGBTQ-affirming counselors when calling or texting 988.[39]

Fully funding the 988 hotline is crucial; a new study found that New Yorkers use the hotline more than those in most other states, ranking fourth out of 50 states.[40] In New York City, Vibrant Emotional Health, the organization that manages the hotline, reported exceeding the number calls and text messages outlined in its contract with the city.[41] Additionally, as New York City has the largest population of LGBTQ+ adults in the country,[42] the city should specifically advertise resources for LGBTQ+ New Yorkers who are in crisis, as well as how to quickly obtain services in an emergency.

Include Peers on Councils and Task Forces

Report Recommendations (2019)

We recommend New York City include peers on all advisory councils and task forces moving forward.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

The city is lagging in the inclusion of peers with lived experiences into the city’s mental health programs and initiatives.

Peers must be included and centered in informing the development and implementation of all mental health-related decisions, programs, and initiatives by the city.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

Though Mobile Crisis Teams may include family peer advocates,[43] the city does not explicitly include peers in crisis response teams, nor every advisory councils and task forces. Advocates and those with lived experience have long advocated for the inclusion of peers in crisis response—especially in the Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division (B-HEARD)—and for the establishment of a Peer Oversight Board “composed of people living with serious mental illness to provide guidance and accountability for the mental health crisis response system and its implementation.”[44] Advocates have called for a $4.5 million baseline allocation to improve compensation and resourcing for peer specialists,[45] which was included in the FY2026 budget.[46]

Implement Mental Health Screenings in Public Schools

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

Approximately 50% of lifetime mental health conditions begin by age 14 and 75% of conditions begin by age 24.[47] We recommend for the NYC Department of Education to implement standardized mental health screenings for children to be evaluated annually whether by a primary care physician or in school. As a preventative measure, early-age mental health screenings can lead to early identification and treatment and may reduce the risk of mental health crises later in life.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

New York City’s public schools are the city’s main youth mental health system.[48] Though the city has continued to invest in student mental health, including opening 16 school-based mental health clinics in 2024,[49] schools are not performing standardized mental health screenings for all students. The Mental Health Continuum—a partnership between New York City Public Schools (NYCPS), DOHMH, and H+H—currently serving students in the South Bronx and Central Brooklyn, could pilot a universal mental health screening for students in their service schools.

In 2023, New York City contracted with Talkspace, an online therapy platform, to launch Teenspace, a free mental tele-health service for youth ages 13 to 17.[50] Though the Adams Administration touted the $26 million program as a success, civil liberties groups raised privacy concerns.[51] [52] The website collects sensitive information from those who sign up, and the New York Civil Liberties Union, Parent Coalition for Student Privacy, and AI for Families sent a series of letters to DOHMH detailing how the Teenspace website shares this information with ad trackers, cookies, and Facebook, Amazon, Meta, Google, and Microsoft, among other companies. While making mental healthcare free and accessible to any student who needs it is important and urgently needed, the city must also ensure that it is properly vetting any companies or providers with which it contracts, and ensure that student privacy is its top priority.

Improving Crisis Intervention Training and Additional Police Department Protocols

Expanding Crisis Intervention Training

Report Recommendations (2019)

The New York City Police Department (NYPD) must train all of its officers who interact with the public in Crisis Intervention Training (CIT). The city must ensure that all police officers receive CIT within an expedited time frame, and that all officers receive annual retraining in CIT. Furthermore, accountability mechanisms must be put in place to ensure that CIT standards are upheld, and that there are correspondingly appropriate consequences when standards are violated.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

In an October 2022 announcement by NY Governor Kathy Hochul in response to subway crime, CIT will be expanded by the State to inform NYPD and other first responders “on the statutory authority for the transport of individuals in need of a psychiatric evaluation at hospitals and [Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Programs]. This training will also incorporate best practices for engaging the street population experiencing mental health illness.”[53]

Within the NYPD, Crisis Intervention Training is a four-day course with over 16,000 officers trained to “recognize the signs of mental illness and substance misuse, and better assist people in crisis.”[54] However, there is no other publicly available information on the frequency of CIT training nor the accountability measures.[55]

The NYPD should publish and make publicly available data on Crisis Intervention Training frequency, the number of officers trained, and how soon they are trained upon joining the NYPD. Ultimately, the goal should be for all NYPD officers to be trained.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

The Crisis Intervention Team training program is still a four-day course at the Police Academy.[56] Between 2015 and 2024, 21,705 active and retired members of the NYPD have been trained in CIT, and all recruits now receive the four-day training.[57] As of September 2024, 77 percent of patrol command officers, 73 percent of housing officers, and 75 percent of transit officers have been trained in CIT.

In March 2025, Police Commissioner Jessica Tisch announced a new training module for 2025 which will expand the NYPD’s CIT to include integrating communications assessment and tactics, or iCAT.[58] This de-escalation training “is centered on the critical decision-making model and will teach… officers additional skills and tactics to better serve them in situations where someone is in mental distress.”[59] This training will begin with the newest Police Academy class and will continue to be rolled out across the NYPD throughout the year.

Thus far, there is no publicly available, continuously updated data on how many officers have received the CIT training—either the four-day Police Academy training or the new iCAT training. There is no public good to a program without available data, especially for an agency with an often-contentious relationship with the community.

Monitoring and Evaluating the CIT Program

Report Recommendations (2019)

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) for the NYPD should lead monitoring and evaluation of the efficacy of CIT training and report on a regular basis.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

There does not seem to be any changes in accountability and monitoring of the NYPD’s CIT. In fact, in 2020, CIT was paused indefinitely with no alternatives in place.[60] As a result, police officers most likely went without CIT at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We are renewing our recommendation for the OIG to lead monitoring and evaluation of the NYPD’s CIT and report results at minimum once a year to ensure all NYPD officers are trained.

2025 Status of Recommendations

There is currently still no independent monitorship or evaluation of the NYPD’s CIT or iCAT training, which makes it difficult to evaluate the efficacy of this program.

Appropriately Dispatching CIT-Trained Officers

Report Recommendations (2019)

It is essential that the city’s 911 technology has the capacity to identify calls that require CIT and dispatch the officers who have appropriate training to the locations where they’re needed.

We recommend the city to improve its training, protocols, and technology so that operators and dispatchers are able to identify mental health crisis situations and send CIT-trained officers on site.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

In 2021, the city launched the B-HEARD. The B-HEARD teams are composed of the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) Emergency Medical Technicians/ paramedics teamed with a mental health professional from NYC Health + Hospitals and can only be dispatched through 911.[61] Data from January through March 2022 showed that 911 Emergency Management System (EMS) operators routed 23 percent of mental health 911 calls to B-HEARD teams. Of those calls, B-HEARD responded to just over two-thirds (68 percent). In total, B-HEARD only responded to about 16 percent of mental health 911 calls in the areas it serves, down from 20 percent in the first month of the pilot. Ultimately, the NYPD still responded to the vast majority―84 percent―of mental health crises.[62]

As we have seen with the avoidable deaths of individuals in crisis,[63] having CIT-trained officers respond is not a guarantee that the situation will be deescalated. While we recommend for all police officers to be trained in CIT, in order to mitigate further harm and deaths, the city should strive for mental health professionals as the default response for mental health crises rather than law enforcement.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

Since the launch of B-HEARD, the number of responses to mental health crisis calls has increased. In FY2024, 40 percent of mental health calls in the areas served by the pilot program were deemed eligible for a B-HEARD response; of these, B-HEARD teams responded to 73 percent, with 29 percent of total mental health emergency calls receiving a B-HEARD response.[64] A recent audit by City Comptroller Brad Lander’s office found that, during the scope period of the audit, 13,042 (35%) of the 37,113 calls determined to be eligible for B-HEARD did not receive program services.[65] The reasons why these calls did not receive services is unknown, as the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health (OCMH) does not track this information.

Though the number of calls receiving a B-HEARD response has increased, it remains at less than a third of the total number of mental health crisis calls. There are a number of reasons that B-HEARD responds to such a small number of these calls, including inadequate staffing. There is a shortage of 911 operators who can appropriately triage the calls—and a lack of staffing in general—leading to a default police response.[66]

Staffing the B-HEARD teams themselves can present a challenge, as these calls can be more difficult and time-consuming to address than a typical EMS call. The city should be incentivizing EMS workers and paramedics to join B-HEARD teams and fairly compensate them for their work with equitable contracts. The city should also be allocating funding directly to Health + Hospitals to hire social workers and mental health professionals for B-HEARD teams. While the city has not detailed what a citywide B-HEARD program would look like, if the program scaled up staffing at the same proportion it had to serve 25 precincts, that would mean just 280 people for all of the city’s 77 precincts, compared to 35,000 NYPD officers.[67] Peers—people with lived experience with the mental healthcare system as well as professional training—should also be included in all B-HEARD teams. If we want an effective alternative to police responses to people in mental health crises, we must be meaningfully prioritizing resources for that response; otherwise, we are endangering not only those who need help but those who respond.

Further Improving Dispatching

Report Recommendations (2019)

We recommend that 911 operators, police dispatchers, and responding officers all need to be able to identify and effectively relay when a mental health crisis is occurring. Additionally, all known information about past police encounters, documented mental health diagnoses, and current behavior patterns must be conveyed to responding officers.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

In addition to the lack of response from B-HEARD teams overall, B-HEARD’s average response time increased from 13 minutes and 41 seconds in 2021 to 14 minutes and 12 seconds in 2022.[68] In comparison, reported response times for NYPD, EMS, and FDNY respond in ten minutes or less. Additionally, callers cannot specifically request a B-HEARD Team.[69]

Dispatch training must be improved to incorporate dispatching for mental health crises through ways such as a mental health solution tree that will branch off into separate dispatching categories for various responses. Mental health training must be conducted regularly to ensure calls are being appropriately dispatched to the right teams.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

The average B-HEARD response time is approximately 20 minutes,[70] which is due to a number of factors. Dispatchers typically have more questions for the caller to appropriately categorize the call, and mental health calls usually have lower prioritization than life-threatening emergencies. Still, it is possible to lower response times to mental health calls, which could very likely be life-threatening.

It is imperative to ensure that 911 dispatchers are properly trained in how to effectively determine which calls can be sent to B-HEARD. Dispatch training must be improved to incorporate dispatching for mental health crises through ways such as a mental health solution tree that will branch off into separate dispatching categories for various responses. Mental health training must be conducted regularly to ensure calls are being appropriately dispatched to the right teams. We can also learn from models in other cities: in Chicago, dispatchers are regularly updated on the outcomes of calls directed to their Crisis Assistance Response and Engagement teams, and other cities have invited dispatchers on ride-alongs to see teams in action, increasing dispatchers’ confidence in these teams.[71]

Integrating Neighborhood Coordination Officers (NCOs)

Report Recommendations (2019)

NCOs are well positioned to provide the NYPD with precinct and sector level information regarding neighborhood residents who have a history of mental health crisis and may be at risk of experiencing similar crises in the future. They can ensure that responding officers have crucial relevant information.

Status of Recommended Action (2022)

NCOs are not necessarily utilized to help address mental health crises. The city had implemented Co-Response Teams (CRT) as pre- and post-crisis intervention with each team composed of two patrol officers and one behavioral health professional to serve community members. However, the program was never linked to 911 and had limitations.[72]

If there is NCO integration, the hyper-local community-based organizations providing social services to the community should be involved in assessing the needs of community members. Guidelines should be established in terms of what information is shared (if any) to the NYPD, including mental health history.

Status of Recommendations in 2025

Earlier this year, Mayor Adams and NYPD Commissioner Tisch announced a new NYPD unit—the Quality of Life Division—to focus on non-emergency, quality-of-life issues like noise complaints, homeless encampments, reckless scooter riding, and outdoor drug use.[73] These teams, called “Q-Teams,” include neighborhood coordination officers, youth coordination officers, and traffic safety officers. The teams initially began with a pilot program in five precincts and one housing Police Service Area (the 13th, 40th, 60th, 75th, and 101st precincts, along with Police Service Area 1).[74] In August, Mayor Adams announced that the Q-Teams will expand to all of Queens.[75]

Though not tasked with responding to mental health crises, the Q-Teams’ mandate to respond to homeless encampments and outdoor drug use makes it very likely these teams will encounter people experiencing symptoms of mental illness and those in crisis. It is worth noting that this new initiative has been met with some skepticism, being criticized as reverting to “broken windows policing” that the NYPD started using in the 1990s, a theory of crime-fighting that has been debunked and linked to discriminatory policing.[76]

New Recommendations

Respite Care Centers

New Recommendations (2025)

We can be more aggressive in having beds set aside for our youth in crisis with more entry points, culturally competent care, and links to more permanent housing.

While the FY2026 budget adds $3 million, the 100-bed capacity remains a fraction of the need; with 20 percent of individuals in NYC jails diagnosed with a serious mental illness and 23,000 nightly DHS shelter residents, demand certainly outstrips supply.[77] [78] [79 - DHS Stats & Reports]

Utilizing Mental Health Review Panels

New Recommendation (2025)

NY Mental Hygiene Law § 31.37 grants the Commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health the power to establish a mental health incident review panel, either by their own initiative or at the request of a local government unit following a serious incident involving a person with mental illness.[80] However, since the law went into effect in 2013, no municipality in the State of New York has ever requested the convening of such a panel, which can assist the city and state in identifying if gaps in services contributed to an incident and in addressing broader systemic failures following an incident.[81]

A mental health incident review panel includes representatives from the State Office of Mental Health and the chief executive officer or designee of the local governmental unit where the incident occurred.[82] It may also include representatives from service, healthcare, and emergency response agencies. The purpose of the panel is “to identify problems or gaps in mental health delivery systems and to make recommendations for corrective actions to improve the provision of mental health or related services, to improve the coordination, integration and accountability of care in the mental health service system, and to enhance individual and public safety.” In short, to identify the shortcomings that contributed to the incident and how to ensure it does not happen again. This procedure is the opposite of involuntary commitment: instead of attempting to sweep an individual out of sight and into a system that has proven to be lacking, the panel invites people to openly collaborate to the benefit of everyone.

Review the Expansion of Involuntary Commitment Criteria

New Recommendation (2025)

As part of the FY2026 New York State budget, Governor Kathy Hochul insisted on expanding the criteria to involuntarily commit someone for psychiatric treatment, a change for which Mayor Adams had also long advocated. Now, the interpretation that a person is unable to care for their basic needs—not just that they present a danger to themselves or others—is enough to involuntarily take a person for mental health evaluation, a tool which, while important, should be a last resort. With this law now in place, we need forceful oversight to prevent abuses, to determine whether people in the field can accurately, fairly, equitably assess individuals under the new criteria and provide help rather than perpetuate harm. It is also critical to ensure that when someone is hospitalized, they are placed on a continuum of care. It is that long-term investment of time and resources that can help prevent a revolving door of misplaced commitments.

In July, President Donald Trump signed an executive order titled “Ending Crime and Disorder on American Streets,” which, broadly, encourages states to remove homeless encampments and force people into mental health treatment.[83] [84] It conflates people living on the street—especially those in mental health crisis—with crime and disorder. Far from compassionate, data-driven approaches to homelessness and the mental health crisis that we know work, this executive order and the expanded involuntary commitment criteria further criminalize poverty and sweep people experiencing homelessness, mental illness, and substance use disorders into institutions and the criminal justice system.

Pass the Treatment Court Expansion Act

New Recommendation (2025)

Too often, people with mental illness are funneled into the criminal legal system. New York City’s largest mental health facility is Rikers Island, with over half of the jail population having a diagnosed mental health concern, and more than a fifth having a serious mental illness.[85] New York State Senate Bill S4547,[86] sponsored by State Senator Jessica Ramos, and Assembly Bill A4869,[87] sponsored by Assembly Member Phara Souffrant Forrest, is known as the Treatment Court Expansion Act (TCEA). The TCEA amends Criminal Procedure Law Article 216 of the judicial diversion law to expand eligibility for treatment for court-involved people.[88]

The Treatment Court Expansion Act:

Expands New York’s judicial diversion law by including people with mental health challenges, intellectual, neurological, physical, and other disabilities, who can benefit from treatment.

- Ensures that treatment court participants are not jailed without due process.

- Eliminates coercive and ineffective mandated treatment by permitting participation in treatment court without requiring a guilty plea.

- Expands eligibility by eliminating charge-based exclusions.

- Encourages judges to strongly consider the best clinical options for each participant and prioritize behavioral health needs over punitive responses.[89]

The New York State Legislature should pass and the governor should sign the TCEA.

Improve Discharge Planning

New Recommendation (2025)

Under the New York State Office of Mental Health regulations, MHL § 29.15, which mandates discharge planning for people“admitted to inpatient psychiatric services, does not apply to people who are brought in for psychiatric evaluation.[90] Often, people transported involuntarily to a hospital are not admitted inpatient, and are instead kept briefly for observation before being released without a comprehensive follow-up care plan. It is unrealistic to expect people in crisis, and especially those who are homeless, to navigate the complex mental healthcare and housing system without the assistance of a case manager or dedicated clinician to assist with follow-up care and services. The city currently does not track what happens after a person is transported to a hospital, so it is unknown how many people involuntarily removed to a hospital have been connected to long-term treatment and services, or if they were admitted inpatient. The city should collect this data to get a clearer picture of how this expanded involuntary removal criteria is impacting New Yorkers caught in it.

Acknowledgements

Lead author: Gwen Saffran, Senior Legislative and Policy Associate

Additional Support was provided by:

Rosie Mendez, Director of Legislation & Policy

Veronica Aveis, Chief Deputy Public Advocate for Policy

Jeffrey Severe, Deputy Public Advocate for Justice & Safety

Kevin Fagan, Director of Communications

William Gerlich, Special Advisor for Communications

Matthew Carlin, Deputy General Counsel

Elizabeth Guzman, General Counsel

Branson Bailey, Intern for Legislation & Policy

Isidro Borges, Intern for Legislation & Policy

Design & Layout: Luiza Teixeira-Vesey, Digital Marketing Specialist

Thank you to: Rama Issa-Ibrahim, Center for Anti-Violence Educate

Jordyn Rosenthal, Community Access

This report can be translated into over 100 languages at no cost. Please contact us at officeadmin@advocate.nyc.gov for more information.