Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

While conservatives use the phrase ‘DEI’ as a stand-in for any problem in the country, from train derailments and wildfires to flight delays and military operations, it’s worth reminding people what those letters stand for. If you’re against Diversity, Equity, or Inclusion, have the courage to say so.

In New York City, we have long strived to celebrate diversity, recognizing it as a strength for not only our culture, but our economy. Small businesses built by immigrants, minorities, and women are at the core of our economic identity in this city. These M/WBEs (Minority and Women-owned Business Enterprises), despite their essential status, often face systemic barriers that prevent their growth and success in favor of the kind of big businesses and megacorporations that permeate our city from Wall Street to Times Square. We can and must do a better job in our city of promoting M/WBEs, the entrepreneurial spirit and opportunity that drives them.

This report covered Diverse Entrepreneurial Inclusion, a new DEI, built on the same principles and applied to specific programs that our city can improve and invest in to lift up historically marginalized groups and enterprises. Bolstering M/WBEs, supporting diverse entrepreneurs, is both socially and economically responsible, and in the city which serves as an economic engine for the world, this is an opportunity we have to embrace. As a former small business owner myself, I know firsthand the challenges faced in building and sustaining a business, the possibilities for government to lessen those burdens and provide support through barriers, and the obligation to proactively pursue these policies.

Many of the same critics that attack DEI principles are currently fanning the flames of hysteria about the incoming administration and its economic agenda, claiming it will harm businesses. But as this report demonstrates, the truth is that this can be a new era for business in New York City – strengthening the small and diverse businesses we are fortunate to have today, and supporting the entrepreneurs of tomorrow.

Sincerely, Jumaane D. Williams Public Advocate for the City of New York

Background

Over 62,000 small businesses started between October 2021 - September 2023, and there was also a rise in sole proprietorships or solopreneurs.

As New York and the rest of the country continue to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the brightest lights on our path forward is the resurgence of small businesses. Over 62,000 small businesses started between October 2021 - September 2023, and there was also a rise in sole proprietorships or solopreneurs.[1] The New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC) released a report in May of 2024 which showed New York City has more small businesses than ever before[2] even in the midst of a housing crisis, a migrant crisis, and challenges from policy changes of one mayoral administration to the next.

The development and sponsorship of “minority-owned business” has been a focus of government since 1969 when President Richard Nixon helped to create the Office of Minority Business Enterprise through the signing of Executive Order 11458.[3] In the 1990s, New York City Mayor David Dinkins created the Minority and Women-owned Business Enterprises (M/WBE) program that was disbanded in 1994 by his successor Mayor Rudolph Giuliani.[4] In 2005, the New York City Council passed legislation, Local Law 129-2005, where the M/WBE program was codified into law.[5] New York City has since assisted M/WBEs by granting access to contracts and procurements that help those businesses gain capital, as well as additional opportunities to provide their goods or services. In part due to significant economic shifts in traditional industries into 2025 including the Great Recession, market instability, and the continued impact of the pandemic, many small businesses in New York City are now women- or minority-owned. These businesses should have better access to M/WBE contracts.

In recent years, the city has implemented a number of initiatives and policies that have reshaped our streets, such as: pedestrian plazas, bike lanes, and even congestion pricing and other elements that promote less traffic congestion and increased walking or public transportation and the sharing of public spaces. All of this creates more foot traffic and helps small businesses thrive. These are all positive steps, but the city can do more to reinvigorate its people and culture. New York City is the home of Wall Street, Hip-Hop, the Theater District, the New York Mets and Yankees, as well as museums and many other cultural institutions. One way to reinvigorate our city is to create additional opportunities by awarding more equitable contracts to eligible M/WBEs. With new leadership taking over City Hall on January 1, 2026, New Yorkers can look forward to conversations on how to best support M/WBEs and all small businesses with Mayor-Elect Zohran Mamdani and his incoming administration.

Uplifting Businesses

Historically, New York City’s (NYC) small businesses have played a vital role in our economy. The Department of Small Business Services (SBS) is charged with providing opportunities for economic security and long-term success for New Yorkers with small businesses. Among other things, NYC Small Business Services (SBS) is tasked with connecting New Yorkers to jobs and training, as well as certifying that vendors meet the criteria to be designated as a Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprise (M/WBE). Businesses owned by people of color and/or women who want to compete for local government contracts are required to apply to SBS and must meet the criteria as set forth by SBS to become a “City-certified” M/WBE.[6]

The NYC Small Business Services (SBS) website provides a wealth of information to support small businesses in general and provides assistance in the M/WBE city-certification process with a M/WBE Document Checklist that outlines all the paperwork needed to apply.

City-certification grants eligible M/WBE small businesses access to the city resources including:

- An opportunity to be selected for discretionary contracts;

- Access and opportunities to industry-specific or general business support;

- Visibility to other potential partners or clients;

- An opportunity to grow one’s business via government contracts and broaden customer base to include the government as a customer; and

- Being listed in the NYC Online Directory of Certified Business[7] which consists of over 10,000 businesses spanning important industries such as childcare, accounting, plumbing, and construction.

A business must be operating for at least one year before being eligible to apply for M/WBE certification by the city, and at least 51% of the business has to be owned and operated by a U.S. permanent resident or citizen who is a woman or a member of a minority group[8]. Eligible businesses can apply for free, but must:

- Have a Federal Tax Identification Number; [9]

- Be a registered vendor with the City of New York ;[10]and

- Have an account to the Procurement and Sourcing Solutions Portal (PASSPort)—New York City’s procurement platform.[11]

SBS provides networking and collaboration opportunities for M/WBEs and small businesses by creating workshops and offering job readiness services. The agency has been making more of a presence in the city by planning events such as the NYC Small Business Month Expo.[12] This kind of effort provides small businesses a chance to expand services and make mutually beneficial partnerships citywide. For instance, small business owners often need legal assistance when dealing with commercial lease agreements and other contracts and business matters. After the COVID-19 outbreak, SBS held workshops and webinars offering M/WBE Contract Legal Services and other informational sessions to help owners stabilize and/or strengthen their business.[13]

Rising costs, increased taxes, and heightened competition, particularly from the pandemic-driven growth of e-commerce, have significantly impacted many eligible M/WBEs in NYC.[14] E-commerce has reshaped specific NYC markets, notably logistics and delivery, transforming the city into a national hub for online goods warehousing.[15] Additionally a variety of NYC businesses, including street vendors, home-based solopreneurs, and those in face-to-face industries like hair care, social media/internet services, food, cannabis, caregiving, and nightlife, face exclusion from the formal economy due to difficulties in obtaining business licenses.[16]

Despite these challenges, NYC has shown a strong commitment to M/WBEs, awarding a nation-leading $6.3 billion in contracts to these firms.[17] However, with M/WBEs currently securing only 5% of annual City contracts, there is significant room for program improvement. SBS is ideally positioned to spearhead these improvements.

Expanding Opportunities

A May 2023 report from New York State Comptroller Thomas DeNapoli’s office highlighted the uneven post-pandemic workforce recovery for Black mothers in New York City. The report noted a disparity in City contracts, stating that “women-owned firms lag those owned by men in terms of number and value of registered contracts with the City. In addition, among women-owned business enterprises that were awarded contracts, the majority were owned by White women.”[18]

To address this inequality, the State Comptroller’s office suggested that “The City and State should also continue to encourage employment opportunities to support mothers in the workforce looking for flexibility.” This includes “enhanced outreach to women-owned firms, particularly those owned by non-White women, to increase their rate of M/WBE certification and improve opportunities for new business.”[19]

Small businesses, particularly M/WBEs, face a competitive disadvantage when pursuing city contracts compared to larger, longer-established, and often national or international corporations. While competition is essential for reducing costs and improving market performance, M/WBEs often lack the dedicated staff and resources that larger businesses utilize to research, draft, and respond to complex Requests for Proposals (RFPs). Furthermore, bigger businesses possess established industry knowledge and relationships that smaller M/WBEs have not yet had the opportunity to build. Therefore, M/WBEs require additional support to truly compete effectively for these contracts.

In February 2025, NYC Comptroller Brad Lander published the Annual Report on M/ WBE Procurement: Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Findings and Recommendations. The report stated that many M/WBEs shared frustration at the length of time and the complicated nature of the process to obtain city-certification.[20] This process is frequently delayed due to employee understaffing at SBS that hinders the review of applications.[21] Many applicants fail to meet eligibility requirements, primarily due to incomplete paperwork.[22] This delay in notification slows the process further, when more documentation is needed. Both the state and city have been impacted by this issue.

In response, the state invested $11 million to streamline the M/WBE application process, addressing a certification backlog that occurred in 2023.[23] Despite the Adams administration’s announcement of over $6 billion in M/WBE contracts awarded in (FY24), the Comptroller’s reports indicate ongoing problems. These include sluggish payments and a low overall utilization of M/WBE contracts. As of FY24, the Comptroller’s report highlighted that M/WBEs received only 6% of city contracts. Furthermore, within this 6%, a significant disparity exists with individual minority groups each securing merely 1% of the city’s total contract value.[24]

Governance

The NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) awarded 407 contracts worth a total of $432 million to M/WBEs in the last three years.

Annual reports from the NYC Comptroller’s office since FY22 have consistently highlighted a lack of improvement in addressing disparities with M/WBEs, a trend observed over the past three fiscal years. The Comptroller’s reports also point out that the average value of M/WBE contracts remains low.

However, city agencies like the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC)[25] and the Department of Transportation (DOT)[26] have testified at NYC Council hearings that they are increasingly surpassing and exceeding their M/WBE goals. In FY25, the city’s M/WBE program, operating under Local Law 1-2013, achieved a record utilization rate of over 36% for contracts covered by this law. This translates to more than $2.2 billion in contracts awarded to M/WBEs. This raises several questions. What was the initial goal? What exactly is being done to increase average values of contracts to acceptable levels?

The NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) awarded 407 contracts worth a total of $432 million to M/WBEs in the last three years for agency eligible projects. [27] However, other city agencies cannot say the same. Many eligible small businesses are becoming city-certified and joining the M/WBE program in larger numbers than before, all city agencies should consider reviewing their own contracting process.[28] The incoming Mamdani administration can direct every city agency to grant a minimum number of contracts to M/WBEs.

In 2015, the de Blasio administration established three key “OneNYC” objectives including awarding 30% of Local Law 1-eligible (LL1) contracts to M/WBEs by FY21, allocating $25 billion citywide to M/WBEs by the close of FY25, and certifying 9,000 M/WBE vendor firms. The number of certified M/WBEs has almost tripled from approximately 4,500 in 2016 to over 11,000 as of the third quarter of FY24.[29] There is a need for NYC to spread the equity of M/WBE contracts across all city agencies and it has the ability to do so.

City agencies, at times, are not able to provide the programs, services, and opportunities once provided due to budget and fiscal constraints imposed by this administration and its predecessors. These agencies can be supported by M/WBEs and other small businesses, especially if they know where to find the specific M/WBE or service they need through substantive community engagement.

For example, the NYC Department of Education contracts with private businesses for a variety of services that includes meals and transportation. Students with disabilities are required to receive a Free Appropriate Public Education under federal law. Many students in the NYC Public Schools (NYCPS) have been experiencing delays in receiving services, evaluations, and in developing Individual Education Programs (IEPs).[30] The NYCPS tends to contract with major corporations outside of city and state jurisdiction to try to meet the demand of services not being met, rather than connect with local service providers.[31]

It appears there is a pattern in Mayor Adams’ administration to utilize emergency waivers to justify using non-NYC and non-M/WBE contracts for major NYCPS programs such as NYC Solves and NYC Reads.[32] The Adams administration spent over $1 billion of taxpayer dollars on emergency no bid contracts at the outset of the migrant crisis.[33] An investigation of the emergency contracts entered into by the Mayoral administration by NYC Comptroller Lander exposed that the vendors utilized as security personnel at migrant shelters were being paid $117 per hour–four times the prevailing wage for such services.[34]

Emergency waivers divert NYC funds to out-of-state, non-M/WBE companies, undermining local businesses. NYC shelters waste food daily due to contracts with providers of unappetizing, culturally irrelevant meals, increasing greenhouse gas emissions and hindering sustainability goals.[35] In some cases, meals that are transported from out of state are spoiled and may have been subjected to improper handling during preparation, storage, and transportation. The people counting on those meals are faced with the indignity of going hungry or eating the unspoiled parts of the meals that they provided.[36]

Utilizing local businesses, especially offering contracts to M/WBEs, could cut out that waste. Larger organizations face less financial impact from providing poor meal service, reducing their motivation to improve their behavior. M/WBE providers could offer culturally relevant, better-tasting food to shelters, reducing waste and emissions while promoting local industry sustainability.

Procurement

Another challenge facing M/WBEs is that more than half of the contracts awarded to them are registered late by the city. According to the NYC Comptroller, “this forces M/ WBEs to advance funds out of limited working capital, to seek to borrow in order to start the project, and delays the start date of many projects. In some circumstances, it means M/WBEs are providing services to the city without any guarantee of getting paid. This is especially challenging given that the average M/WBE contract sizes are smaller than average city contracts, and many M/WBEs are small businesses that lack sufficient working capital and may have a more challenging time borrowing from traditional lending institutions.”[37]

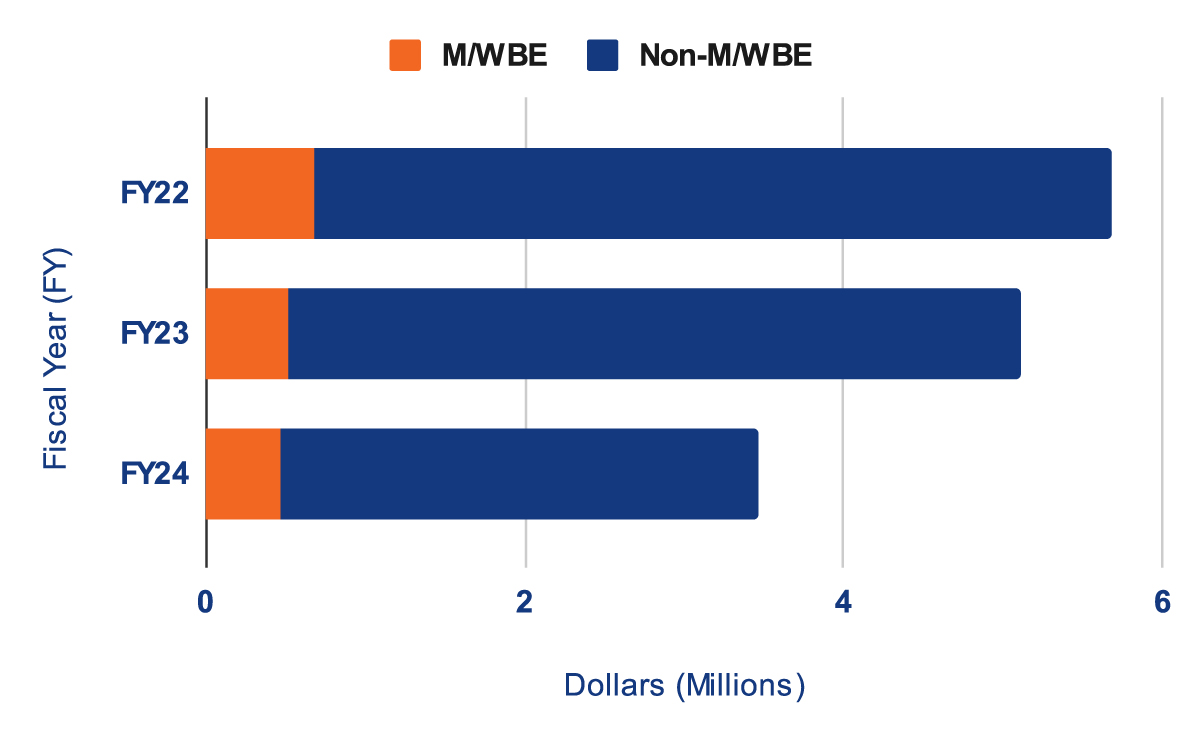

M/WBE vs. Non-M/WBE Contract Amounts (Avg.)[38]

Image: Bar Chart comparing M/WBE vs. Non-M/WBE Contract Amounts. Non-M/WBE surpass M/WBE in millions of dollars every year.

Contracts funded by the state or federal government usually preclude the city from establishing its own M/WBE participation goals, however, the city is free to establish M/WBE participation goals on contracts it funds. 75% of the city’s procurement value consists of “excluded procurement categories” for M/WBEs that includes government to government procurements, awards to not-for-profit entities, and human services procurements. Many of these excluded contracts usually include subcontractors who could be subject to M/WBE participation goals.[39] Going forward, the SBS should work to assist M/WBEs with acquiring contracts for the other 25% of the city’s procurement value that is not in the excluded categories.

Many M/WBE contracts are registered retroactively, which causes those businesses to delay services or borrow funds for operating capital. Though a M/WBE is awarded a contract, they may not receive funds from the contract in a reasonable time frame and could incur huge interest on loans taken out against future payments from the city.

A “pass-through arrangement” in the context of M/WBEs is an illegal fraud scheme where a certified M/WBE acts as a shell company to receive payment for work that is actually performed by a non-M/WBE firm. This is considered a type of “pass-through” fraud because money and project credit are simply being passed through the M/ WBE to a non-certified company, and the M/WBE does not perform a Commercially Useful Function (CUF).[40] City agencies like the Department of Investigation and the Comptroller’s Office actively monitor for such shell companies. M/WBEs that engage in this practice risk penalties and losing their certification.[41] Smaller-sized M/WBEs that struggle with cash flow while awaiting government payments may succumb to the financial strain by joining “pass-through” arrangements.

Oftentimes, this leads to subcontracting, which lacks oversight and is said to have become rife with nepotism and favoritism.[42] In such arrangements, M/WBEs subcontract to larger firms for a small fee, providing immediate cash without incurring debt or experiencing long delays.

A significant issue in the NYC M/WBE program is the inability to hold subcontractors accountable for failing to deliver services or committing outright fraud. This problem stems from a combination of lax oversight, the lack of a direct contractual relationship between the city and subcontractors, and transparency issues in tracking payments and performance. The system heavily relies on prime vendors for self-reporting and compliance, and agencies frequently fail to enforce existing rules, leading to a breakdown of accountability for subcontractors. This self reporting hurts M/WBEs working as legal subcontractors, when they are at the mercy of the business who is on record as contracting with the city to receive timely payments.[43]

M/WBE subcontractors frequently face challenges in receiving timely payments from primary contractors. When the city itself delays payments to contractors, this issue is compounded, making it difficult for contract holders to pay their subcontractors. Furthermore, M/WBE subcontractors often struggle to get reimbursed for their work even after filing complaints with the relevant agency, particularly if they lack the financial resources to hire a lawyer and pursue legal action.

Opportunity

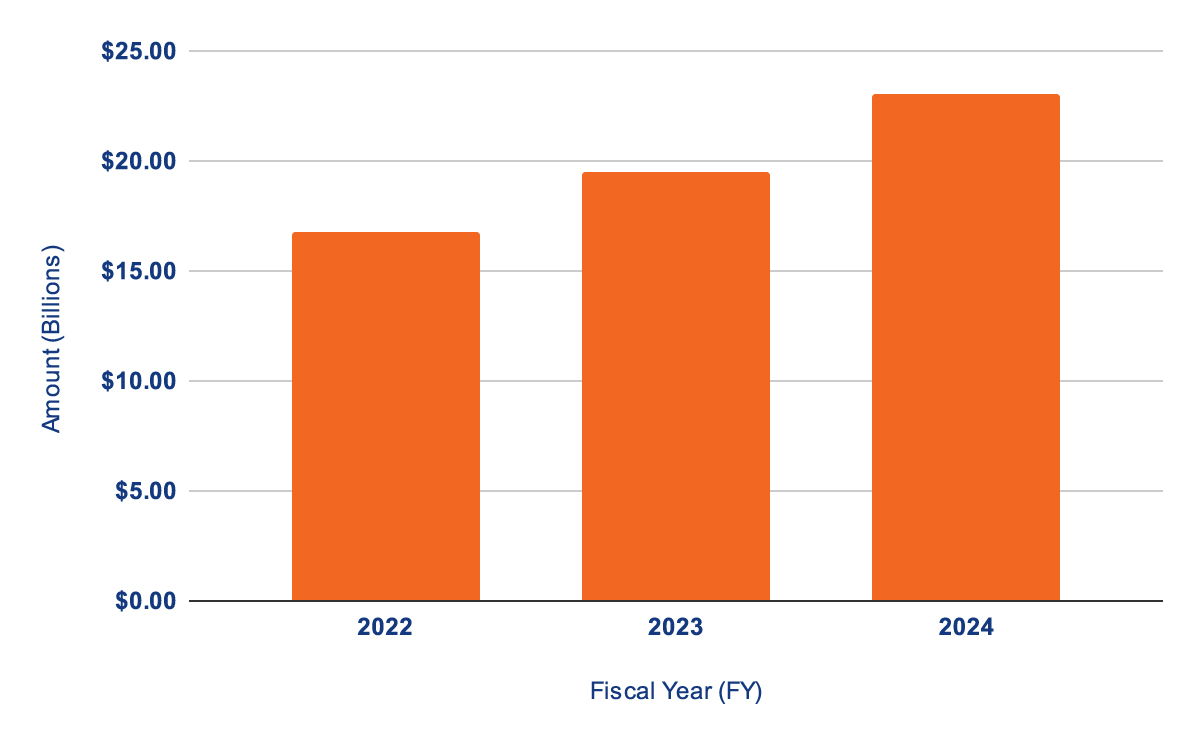

Creating more access and capital for M/WBE’s has brought significant returns specifically regarding the diverse and emerging asset managers covering the city’s five public pensions. Though the annual M/WBE reports from the NYC Comptroller state that M/WBE’s suffered a decrease in an average value of contracts, assets under management by M/WBEs have simultaneously increased over $6 billion dollars, a growth of 40% of assets from the end of FY22 to the end of FY24.[44] This data reveals persistent M/WBE disparities in general procurement but success in pension fund asset management. This suggests the overall M/WBE program faces challenges, while targeted M/WBE asset manager investments are effective. Expanding M/WBE investments to other sectors could yield similar positive results.

Assets under Management by M/WBE Managers[45]

NYC Five Public Pensions

Image: Bar Chart of Assets under Management by M/WBE Managers. Around 15 billion in 2022, 20 in 2023, and 22 in 2024.

To better support NYC’s M/WBEs a fundamental overhaul of existing structures and responsibilities within city agencies is imperative. A primary focus must be on ensuring that the executive staff of SBS fully and effectively fulfills its responsibilities in championing and facilitating the growth of M/WBEs. A significant impediment to the success of the M/WBE program is the presence of bureaucratic hurdles and redundancies that currently exist across the SBS, the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services (MOCS), and the Mayor’s Office of M/WBEs. These overlapping functions and unnecessary layers of approval and oversight often create confusion, delay processes, and ultimately hinder M/WBEs from accessing crucial opportunities and resources. Streamlining these inter-agency workflows and clearly delineating roles will be crucial for improving efficiency and effectiveness.

The Mayor’s Office of M/WBEs, as currently defined, aims to “enhance coordination between city agencies and provide oversight and accountability of the city’s M/WBE Program.”[46] While this mission is vital, the continued necessity of maintaining both the SBS and the Mayor’s Office of M/WBEs, especially with the recent introduction of the Chief Business Diversity Officer (CBDO) role, warrants a comprehensive re- examination. The intent behind the CBDO role is to further improve the city’s M/WBE program, but suggests potential for even greater overlap when the SBS maintains a Division of Economic & Financial Opportunity where work includes helping to provide a pathway for M/WBEs, emerging businesses, and local businesses to do more work with the City of New York through certification, technical assistance, training, mentoring, and capacity building programs.

A critical analysis should be undertaken to determine if the current multi-layered structure is indeed the most efficient and impactful way to achieve the city’s M/WBE goals. This examination should consider whether consolidating certain functions, empowering a single entity with greater authority, or clearly defining distinct but complementary roles for each office would better serve the M/WBE community. The objective should be to eliminate any unnecessary duplication of effort, reduce administrative burdens, and ensure a cohesive, unified strategy for strengthening M/ WBE access and services in New York City.

New York City Charter Revision

In May 2024, Mayor Adams appointed 13 individuals to a Charter Revision Commission (CRC), which subsequently proposed six ballot measures to amend the New York City Charter. Among these, Ballot Question 6, concerning “M/WBEs and Modernization,”[47] was the only proposal rejected by voters on November 5, 2024.[48] The Mayor’s establishment of a Chief Business Diversity Officer (CBDO) position through an Executive Order in 2023 rendered the CRC’s proposal for a similar role unnecessary.[49] The CRC’s proposal aimed for a CBDO to act as an M/WBE point of contact, assess procurement disparity policies, and suggest changes. This function is already partially covered by the existing SBS Assistant Commissioner for M/WBE Recruitment and Eligibility, who oversees the Certification team responsible for processing M/WBE Program applications. A new mayoral administration has the option of either maintaining, modifying or rescinding any Executives Orders of a prior administration, but undoing a ballot measure requires that voters be presented with another ballot measure.

The rapid progression of the Charter Revision Commission’s public hearings and ballot question finalization, occurring between May 21 and July 25, 2024, significantly constrained public review.[50] This swift timeline, which bypassed the New York City Council, resulted in low attendance at hearings.[51] Early voting began a few months later on October 26, 2024, and concluded on November 5, 2024, Election Day. It is important to note that the voters of NYC were able to discern the redundancy and vote against this ballot measure even with the constricted timeline.

Conclusion

Minorities and women, along with people with disabilities, have historically faced systemic employment discrimination. This pervasive issue has often pushed many into entrepreneurship or solopreneurship, not just as an alternative, but as a proactive strategy to achieve greater autonomy, secure economic stability, and pursue meaningful career advancement. When traditional employment sectors present formidable barriers—whether through biased hiring practices, limited opportunities for promotion, or unequal pay—starting one’s own venture becomes a powerful pathway toward financial independence and personal fulfillment.

To truly empower these businesses and ensure their sustained growth, robust support systems are essential. The city has a pivotal role to play in providing comprehensive resources, specialized training, and crucial capital. This support should be multifaceted, offering expertise in areas such as business development, financial management, marketing, and legal compliance. By actively investing in and nurturing M/WBEs, the city can unlock a wealth of economic and social benefits.

Expanding the average value of contracts awarded to M/WBEs is a strategic imperative. These businesses are not just economic engines; they are deeply rooted in their communities. They tend to hire locally, creating job opportunities for residents within the neighborhoods they serve, thereby fostering community wealth and reducing unemployment. Furthermore, the presence and success of M/WBEs bring significant positivity and innovation to the diverse sectors in which they operate, contributing to a more vibrant, equitable, and resilient local economy. Their unique perspectives and approaches often lead to more tailored and effective solutions, benefiting the city as a whole.

Recommendations: Steps New York Should Take

There has been a record of obfuscation by the city around the awarding of contracts which has resulted in beliefs that most M/WBEs are unprepared to fulfill the contracts they seek. Moreover, it has resulted in real harm at times for M/WBEs that have been denied contracts.[52] 52% to 77% of city contracts were registered late over the last three years by the NYC’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which resulted in delays in payments for service providers.[53] These payment delays keep decent service providers in a variety of industries from seeking contracts or M/WBE certification. The average value of new contracts registered to a M/WBE, specifically for Black people, Hispanic people, and Women of Color owned businesses has been low.

Taking the steps outlined below will help M/WBE’s to provide many benefits for the city and its citizens.

New York State should pass the following legislative measures:

- Pass S1087A / A3910, which relates to written notice to unsuccessful minority-or women-owned business enterprise bidders on state contracts.

- Pass S631 / A6962, which relates to the use of M/WBE investments of state funds.

The proposed state bills would require that any municipality within the State of New York make investments of no less than 20% with a M/WBE manager, financial institution, or professional service fund. The NYC Comptroller reported that New York City assets under management by M/WBEs increased by 6 billion dollars from the end of FY22 to the end of FY24.[54] The NYC Comptroller’s independent decision to invest 13% of NYC’s funds with M/WBEs was a success and demonstrates that other municipalities would benefit from doing the same.[55] This work assists strengthening the New York City Employees’ Retirement System and helping to save the city substantial amounts of money that can be reinvested into the public. It further shows how minority and women owned businesses positively contribute to the local economy.

New York City should pass the following legislative measures:

- Pass Int. 0023-2024, which relates to an annual report for minority and women owned business enterprise procurement.

Comptroller Brad Lander has published an annual report on M/WBE procurement since FY22. The city should provide access to these reports to the public after the end of his administration.

- Pass Int. No. 1012-2024, requiring the city to implement and maintain a digital procurement and contract management system thereby creating a centralized and transparent database for New Yorkers to check for bids. This database should also provide the ability to access city services and apply for contracts from city agencies.

- Pass Res 0528-2024,[56 -There is no Assembly sponsored bill accompanying S8497. Both a Senate and Assembly bill is needed and it would need to be voted out and pass through both chambers to become law.] which relates to requiring agencies to provide unsuccessful bidders that are certified minority- or women-owned business enterprises with a written statement of completion of the procurement selection process and that such enterprise was not selected.

The Preliminary FY25 Mayor’s Management Report stated that the M/WBE program newly certified and recertified over 900 additional M/WBEs during the first four months of FY25 and the number of jobseekers registering through the Workforce 1 system (WF1) is up for the first time ever, at an increase of 43%.[57] This upward trend puts more onus on the city and state to provide transparency to M/WBE’s who may later apply for procurements or government contracts.

SBS should create campaigns to recruit minority and women-owned businesses and assist them with applying for M/WBE opportunities at the City level.

While there are 18 Workforce 1 Career Centers dedicated to job seekers and general workforce development, there are only seven NYC Business Solutions Centers (BSCs) focused on serving small businesses and entrepreneurs.[58] This disparity presents an opportunity: the greater number of Workforce 1 Centers across the city can be utilized to connect small business owners to individuals at the BSCs who are looking for employment.

A sustained campaign is necessary to effectively communicate the benefits of M/WBE certification for individuals at local Workforce 1 Centers who may want to start their own businesses. M/WBE licensure signifies a vetted business, and the successful completion of a government contract can improve the reputation of a business and assist in securing future contracts with both government and private entities. BSCs could assist businesses in accessing capital and navigating challenges related to violations, penalty fees, and other fines.

Creating and nurturing relationships between businesses seeking assistance from BSCs and individuals attending the Workforce 1 Centers can create not just a pool of potential employees for the businesses, but can serve as valuable experience for those who eventually want to start their own business.

More Transparency In Contracts and RFP Processes

The Mayor should set actionable agency goals for M/WBE contracts that do not fall under excluded procurement categories. For example, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) aims for 30% M/WBE subcontracting in goods and services contracts and 25% in development projects.59 59 M/WBE Program - Frequently Asked Questions

The Mayor should mandate similar goals for other city agencies across various contract categories.

75% of the city’s procurement value consists of excluded procurement categories for M/WBEs including: government to government procurements; awards to not-for-profit entities; and human services procurements. However, many of these excluded contracts include subcontractors who could be subject to M/WBE participation goals.[60] This leaves a significant amount of funds available to successful candidates. SBS should track how these goals are met or increased annually. Agencies should provide written explanations to the Council, Public Advocate, Comptroller, and Administration when these goals are not met.

- The Mayor and the SBS Commissioner should review the concrete outputs and directives of the SBS and the Mayor’s Office of M/WBEs to consider duplicative programming, and streamline services to reduce costs to the city and enhance the city’s M/WBE programming.

For example, in this review, the administration should make clear that between these two offices (SBS and the Chief Business Diversity Officer of the Mayor’s Office of Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprises) what agency manages educating M/WBEs about the M/WBE Non-competitive Small Purchase Method,[61] where they can be awarded up to $1.5 million from city agencies without formal competition.

The NYC Apex Accelerator, a program under SBS, offers crucial, free assistance to businesses pursuing government contracts. Despite its value, many New Yorkers are unaware of this resource.[62] In FY24, the Apex Accelerator hosted over 100 workshops, providing technical assistance to 1,959 participants and an additional 1,000+ firms interested in city contracts.[63 - Interview with Rogina Coar-Smith, Executive Director, NYC SBS Apex Accelerator & M/WBE Vendor Servicesand Jason Adulley, Director of Intergovernmental Affairs & Special Projects, NYC Department of Small Business Services] The program equips businesses with the knowledge to navigate the complexities of government contracting, offering training and support from System for Award Management (SAM) registration to contract accounting.[64] Therefore, enhanced promotion of this vital and often underutilized resource is essential.

Reform the City’s Contract and Procurement System

- The Mayor’s Office of Contract Services (MOCS) must register contracts in a more efficient manner. Even if payments are dispersed upfront, many providers cannot operate for contracted goods and services if the contract faces delays in registration[65].

As technology changes rapidly and A.I. becomes more accessible to users, MOCS should work with SBS to create training for eligible M/WBE’s on best practices using the PASSPort system. MOCs has been known to offer training by partnering with community based non-profit organizations instead of with the city agency that manages M/WBEs.[66] That said, an example of MOCS working closer with SBS has been seen at the NYC Small Business Month Expo.[67] For MOCS to collaborate more with SBS in addition to non-profit organizations will create additional avenues to outreach to business owners, as well as achieve broader economic goals such as the growth of small businesses and ensuring the city’s spending reflects its diversity.

MOCS developed and maintains PASSPort, the city’s digital procurement platform. Although PASSPort Public and the PASSPort Procurement Navigator are public, many eligible M/WBE’s and other businesses do not know how to access them well.[68]

- To increase accountability and transparency, NYC’s Procurement Policy Board (PPB) should function democratically and its appointees should be subject to the advice and consent of the NYC Council. The PPB is administered by MOCS which, according to the preliminary report issued by the NYC Commission to Strengthen Local Democracy, has developed a pattern of disregarding recommendations raised by PPB appointees.[69]

- The PPB is currently made up of 5 members, 3 appointed by the Mayor and 2 appointed by the Comptroller, and the Mayor also appoints the Board Chair. The PPB should also include two members selected by the Public Advocate, similar to the recommendations made by the NYC Commission to Strengthen Local Democracy regarding the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB).[70]

Return SBS’s budget to FY25’s appropriation [71]

- Funding gaps appear when comparing the FY26 Adopted Budget to what was actually spent in FY25 (“FY25 Spent”).[72] SBS FY25 Spent to FY26 Adopted decreased by 14%. Budget cuts affect staffing levels, preventing SBS from being able to fulfill a variety of agency responsibilities including outreaching to communities and assisting with M/WBE services.

Acknowledgments

Lead Author: Ray Sheares, Legislative and Policy Associate

Additional support was provided by:

Rosie Mendez, Director of Legislation and Policy

Veronica Aveis, Chief Deputy Public Advocate for Policy

Gwen Saffran, Senior Policy & Legislative Associate

Jessica Tang, Senior Policy & Legislative Associate

Ariel Edelman, Senior Policy & Budget Associate

Matthew Carlin, Deputy General Counsel

Kevin Fagan, Director of Communications

Elizabeth Kennedy, Deputy Public Advocate for Education and Opportunity

Guadalupe Hernandez, Education & Opportunity Community Organizer

Design and layout created by: Luiza Teixiera-Vesey, Digital Marketing Specialist

Cover Image: Diva Plavalaguna, Pexels

Photos: Ray Sheares, Legislative and Policy Associate

The Office of Public Advocate would also like to thank:

Mark Caserta, Vice President of Small Business Support, Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce

Jennifer Stokes, M/WBE & Legal Services Account Manager, Brooklyn Business Solutions Center of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce

Lindsey Vigoda, New York Director & National Quality Jobs Policy Director, Small Business Majority

This report can be translated into over 100 languages at no cost. Please contact us at officeadmin@advocate.nyc.gov for more information.